The Legacy Museum in downtown Montgomery, Ala. is a large, impressive site, stretching across a full block. It’s complete with large public spaces and a sparkling restaurant serving traditional Southern dishes. As one soon learns inside, the building is also feet from the river upon which ships bearing enslaved people arrived, and a place they were housed and forced to work in shackles. Its bricks, and those of many buildings in the region, were produced and laid by enslaved people.

I traveled to Montgomery specifically to visit the Equal Justice Initiative’s (EJI) Legacy Sites and drive the state. I read founder Bryan Stevenson’s best-selling book Just Mercy some years ago — which focuses largely on his work as a lawyer, representing death row inmates — and have since been inspired by his commitment to reframing popular narratives of United States history.

The genius of Stevenson and his Equal Justice Initiative’s work is placing America’s history plainly before you, in the everyday. Economics, infrastructure, neighborhoods, wealth disparity, violence, incarceration, even the very bricks sheltering us, often find their roots in the enslavement of Black people. The philosophy seems to be that if we know exactly where things happened and precisely to who, we stand a better chance of contextualizing, remembering and reckoning with those truths today.

The museum itself takes you on the journey from capture in Africa and the dangerous middle passage across the Atlantic, to trading of enslaved people and emancipation, to segregation and civil rights, to the war on drugs and mass incarceration. It traces the United States’ economic foundation in slavery from the ports and banks of the Northeast, into the fields of the deep South and beyond, and the unbearable cost for those enslaved. Using a mixture of video presentations, photographs, newspaper clippings, testimonials, holograms, fine art, music and artifacts, the museum shows how this cruel subjugation has never really ended, only changed form.

It was busy when I visited and most people ventured through alone, taking their time in front of various exhibits. In one, a wall of jars filled with dirt from the sites of lynchings provides a literal grounding of the subject. Visitors were of various ages and ethnicities, but universally the staff I encountered at both Legacy sites were Black.

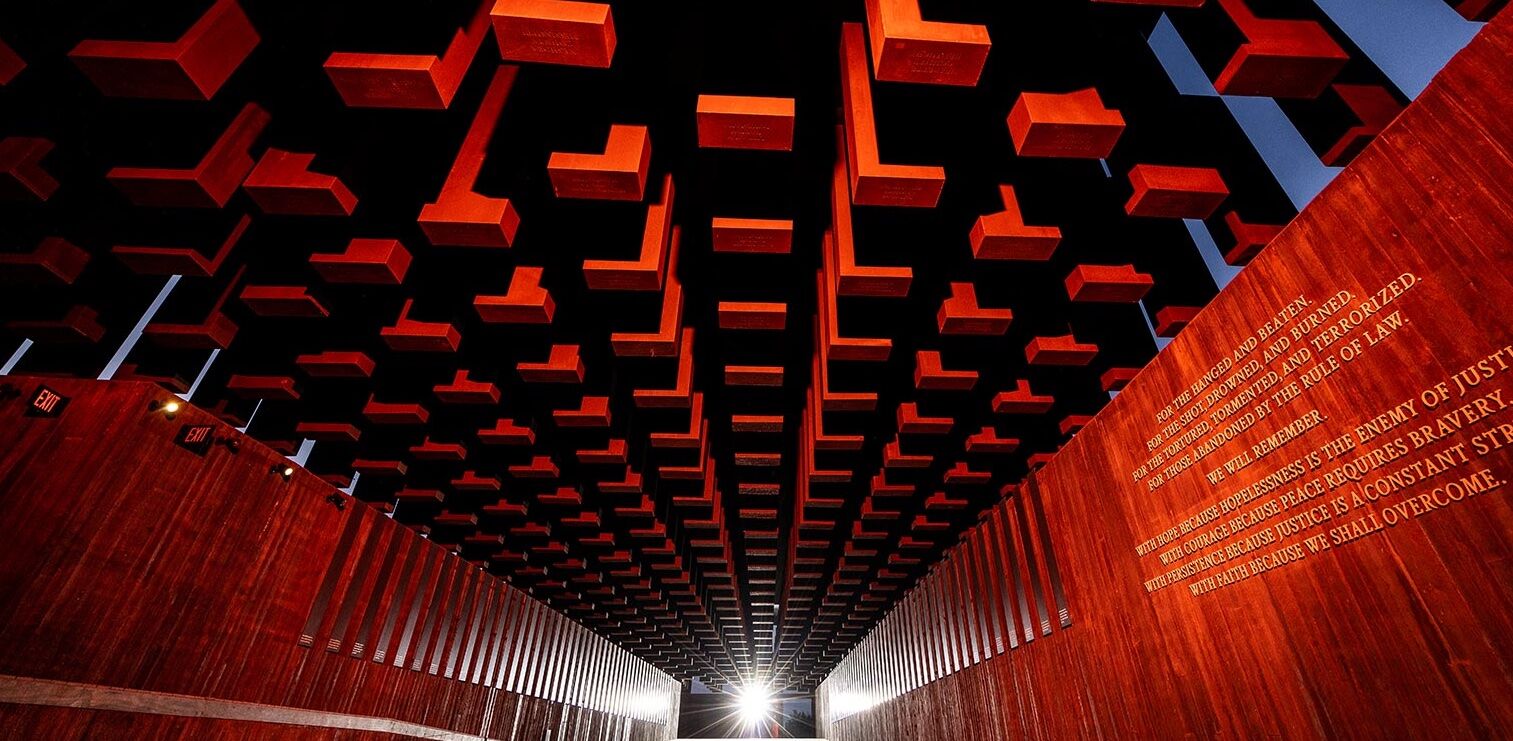

I saved my visit to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice until the next day, arriving in the morning before many other visitors. Perched on a hill, at the center of a six acre lot, the Memorial serves mainly to recognize the more than 4,400 lynchings between 1877 and 1950 documented by the EJI, and estimated 6 million Black people who fled Southern states as a result of this terror.

Incidents are separated into US counties. Each county represented by a six foot corten steel box (more than 800 in total), etched with the dates of the lynchings and names of victims, or simply “Unknown”. Most hang from the ceiling, and as you walk further into the Memorial, the ground slopes down and the monuments slowly rise up, until they’re suspended above you. The impression of bodies hanging from trees, as you read short descriptions of their murders, is impossible to ignore.

Taking a moment in the central, lowest part of the Memorial building, I sat across from a wall of falling water, alone but for a couple of guards. Surrounded by so many names of the dead, organized in that way, brings the length and depth of generational pain inflicted upon countless Black Americans into a deeply moving focus. Outside the markers are duplicated, now laid down so that the places, names and dates may be more easily read. Row after row, stretching along the hillside in avenues. The tour ends with replicas of information posts the EJI has helped erect all around the country, marking sites of lynchings.

Earlier that morning I had explored a very different history, in a humble shopfront, boldly labeled HANK WILLIAMS MUSEUM. It was quiet inside, but for the twang of steel guitar from small speakers. I was the only person in the modest space, crammed full of country music memorabilia, smiling white faces and lovesick songs. It smelled like a grandparent’s living room, and looked it too, but for the huge, baby blue Cadillac convertible in the center of the room. The very vehicle in which Hank died sleeping.

On my way out, the young white woman up front asked, “What brings you to town?” When I told her, she asked me what I thought of the Legacy Museum. I said it was incredible, and she nodded, before giving me directions, unprompted, to Hank’s statue down the street and gravesite a mile or so away.

As I left the museum a tour guide spoke to a group of people on the sidewalk next door. Above them a sign read Equal Justice Initiative. This was another of the many buildings the organization has acquired in town as Stevenson’s mission grows, and a plaque recognized it as a former warehouse for enslaved people. Here was the other side of the story. Just like flipping a record.

Hank’s grave was well-marked by roadside signs as I drove toward it. Again I was the only one there, rain clouds were rolling in over the cemetery, and I was on my way without ever killing the engine.

Back at the hotel, I took a museum information sheet from my pocket and read that from the age of eight, Hank was taught guitar and mentored by a Black street musician named Rufus “Tee-Tot” Payne. The Williamses paid him for the lessons in food. Rufus was born on a plantation and the name Payne belonged to its owners, I later learned. He died in a charity hospital in 1939 at the age of 56, a generation before the Civil Rights Movement would change Alabama forever. He is buried in an unmarked grave, somewhere in the Lincoln Cemetery, on the edge of Montgomery. As are his songs.