It was Friday, the first day of the 25th annual Black Forest Star Party (BFSP), and all anyone could talk about was the weather. As with any outdoor-related activity, a star party is at the whim of Mother Nature, and the forecast was bleak: while the afternoon skies were blue and it was bright, it’s forecasted to rain all night into Saturday morning and be cloudy the rest of the weekend. But the BFSP is held every year, rain or shine, and so I found myself setting up a tent, hoping the good weather would hold and my almost 300-mile drive to northern Pennsylvania was not in vain.

After all, if you don’t see any stars, can you really say you’ve been to a star party?

Something that should have been obvious to me and yet wasn’t before the trip: star parties are held in the middle of nowhere. The best conditions for stellar observations are as far away from civilization’s lights as possible. Since its inception in 1999, the BFSP has been held in Cherry Springs State Park, an 82-acre patch of land in the mountains of northern Pennsylvania that’s at an elevation of 2,300 feet and accessed by a twisting two-lane highway with more sharp turns than you’ve dealt with before. Back when the BFSP was in its infancy, it actually helped remote Cherry Springs become famous, or at least sufficiently well known to keep the park from being decommissioned. “It is not an exaggeration that the Black Forest Star Party kept Cherry Springs from going extinct,” said Joe Broniszewski, co-founder of the Central Pennsylvania Observers, the astronomy club that runs the party.

The partnership between the star party and the park has only gotten stronger through the years, according to Broniszewski, as park officials saw the potential of astrotourism. In 2000, the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources declared Cherry Springs the state’s first dark sky park, and in 2007 the International Dark-Sky Association (now known as DarkSky International [DSI]) certified it as its second International Dark Sky Park. Getting certified is a “vigorous process” that can take more than a year, said Bettymaya Foott, an engagement associate for DSI. A park must not only offer public access at night and meet the requirement for having dark skies, but it must also offer outreach and educational programs for the community.

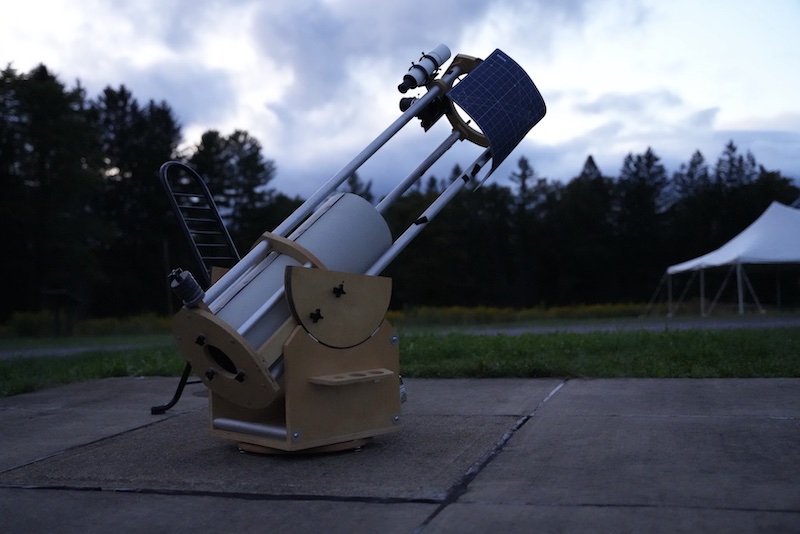

After I checked in at the registration table and set up the tent I borrowed from a co-worker, I wandered to check out my temporary home. BFSP has sold out every year since it launched and it only took a couple of hours for the tickets to get snatched up in 2024. As I looked around, the overnight astronomy field was dotted with dozens of brightly colored tents, a healthy number of campers and RVs, and several telescopes ranging in size from small and easily portable to the size of a Saint Bernard. Sadly, the telescopes were wrapped in plastic to shelter them from the coming storm.

Everyone I spoke to had been set up in the park for a couple of days, and they all told me how gorgeous it was the entire week, right up until I arrived. I tried not to grind my teeth. But the weather was still nice, so maybe the forecasts were wrong?

As soon as the sun set on the field, the rain started. With no stars out and thunder and lightning all around me, I gave up and tucked myself into my tent. It should be noted that I am a certified city girl and definitely Not A Camping Person; I really wished I had rented something that had walls and a ceiling. I spent the evening Googling if a tent can fly away with a person in it and prayed that the tent spikes were correctly harnessed. Thankfully, despite the deluge that lasted all night, the tent did not leak.

The past year or so has brought a mass of articles by everyone from National Geographic to Yahoo! to Condé Nast Traveler about how much astrotourism has grown throughout the world. Part of that is because we’ve had a lot of big astronomic events, like solar eclipses and Northern Lights that could be seen in Florida. Foott said she’s seen an increase in the interest in astrotourism over the years and thinks COVID also played a part: “[People] started going outside and looking up.” Both Broniszewski and Foott said that star parties can be a great way to learn more about astronomy or just to stare into the beautiful night sky.

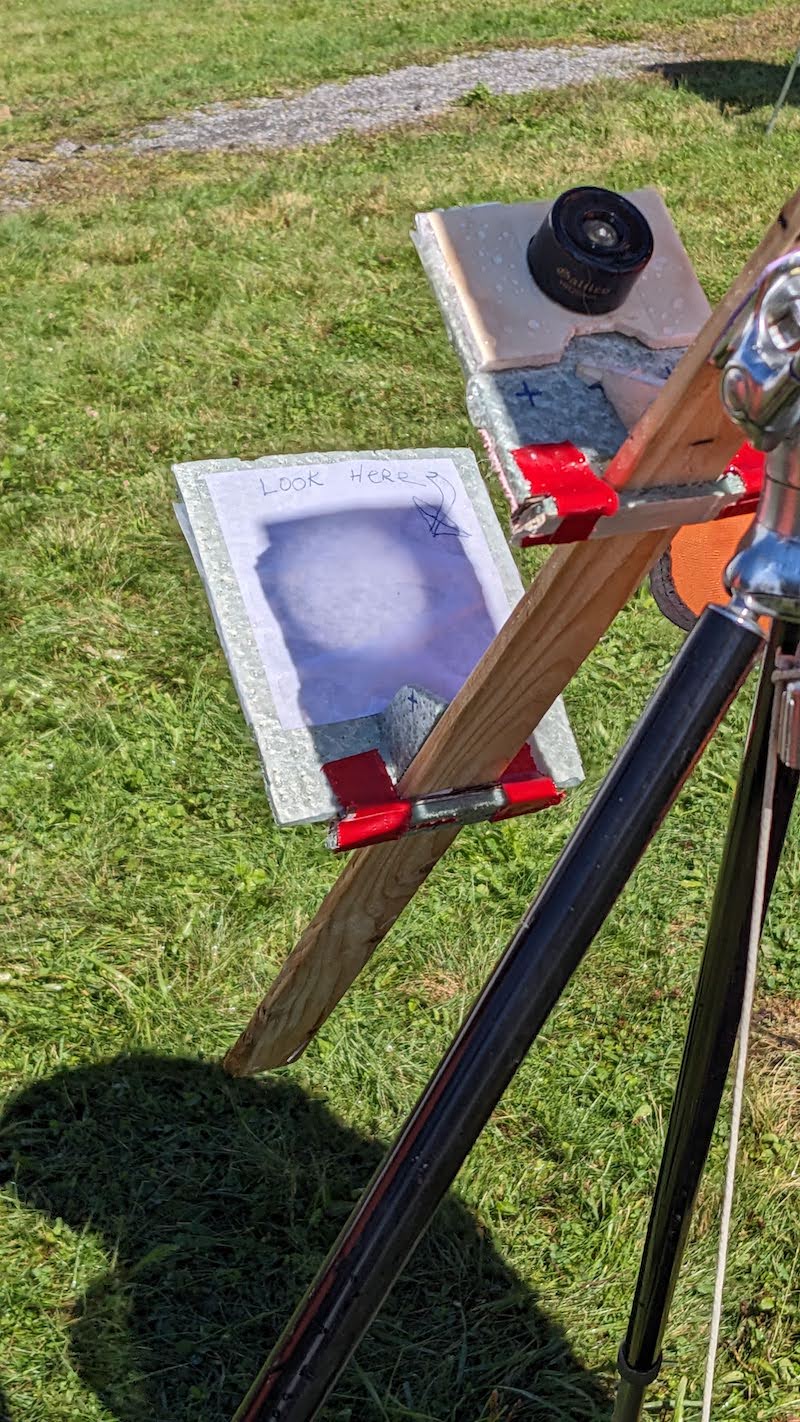

“People who go to the star party are typically very friendly, very education oriented,” Broniszewski said, something I can wholeheartedly agree with after my weekend. Everyone I met seemed excited to see old friends, relax and, of course, indulge in astronomy. Even though a star party’s main activity is during the night (ahem, except in cases of bad weather), BFSP offered plenty to do when the sun is out. A solar viewing station was set up in front of the registration tent, and the owner, Tom Kasner, adjusted it so I could see a projection of the sun on a piece of paper (don’t look directly into the sun, folks!).

After gazing at the only star I might get to see, I wandered over to where a crowd had gathered around Rick Gilmore, who was giving a demonstration of his radio telescope setup. Gilmore, a fellow star party first-timer, said it’s a great intersection between two of his interests: ham radio and astronomy. The group of observers, clearly more knowledgeable than I was, asked questions as we all stared at the readouts on the computer screen.

In the afternoon, several talks covered everything from space junk to Galileo to theories about how the moon formed. The park’s pavilion was packed with an eager audience, and all three speakers, including an astronomy professor, were informative and engaging. After the talks, while a raffle was held, I decided to grab some food from the on-site food truck, Stellar Foods, of course. There were still a few hours to go before evening. It continued to rain on and off. Several campsites emptied out after the raffle, their owners giving up on the chances of a good stargazing night. My nerves frayed as the afternoon dragged on.

As the sun set on day two of the party, a small sliver of optimism spread through the crowd. The moon popped up in the sky. Clouds were still there, but they moved fast. People started to unwrap their telescopes. I walked the field and asked questions about travel gear versus setups at home, and if we’re going to get lucky with the weather. Dusk turned to darkness; I grabbed my camera, crossed my fingers and hoped.

Then I saw it: a star!

And another!

Then, so many more. The sky, which had been described to me on Friday as “velvet black,” was awash in more stars than I’ve ever seen before. My neighbor, who set up his telescope in front of his camper, beckoned me over to get a glimpse of Saturn. I saw satellites crossing against the sky, and the Big Dipper just above the tree lines. Wait, was that…? The huge smear of light in front of me was the Milky Way. Giddy with joy, I found a spot that had been vacated by someone leaving early and got to work shooting photos.

After I had enough, I sat back on the wet grass. I knew I should walk around, glimpse through telescopes and binoculars and interview people, but at this moment, all I wanted was to look at the sky, at the vastness of space and the countless stars. Seeing so much of what’s in space beyond reach reminded me how small humanity is in the grand scope of things, and how much beauty there is in the darkness.

Also, that I need to rent an RV next time.