This story is part of the Fall Travel issue, which is on sale here.

Midday’s blue skies had turned an ominous gray by the time the giant was resurrected. He rose slowly, lifted from his shoulders by straps attached to a forklift. When he finally reached vertical, his feet lifted off the trailer he’d arrived on, and he jerked in the air. For a moment, it seemed as if he might topple onto the crowd below, but then two men grabbed him by his toes and, with some effort, steadied him. Slowly, they guided the giant over to a concrete pedestal, where he was set down and bolted into place, his right hand raised in greeting, his smiling head poking above the rooftops.

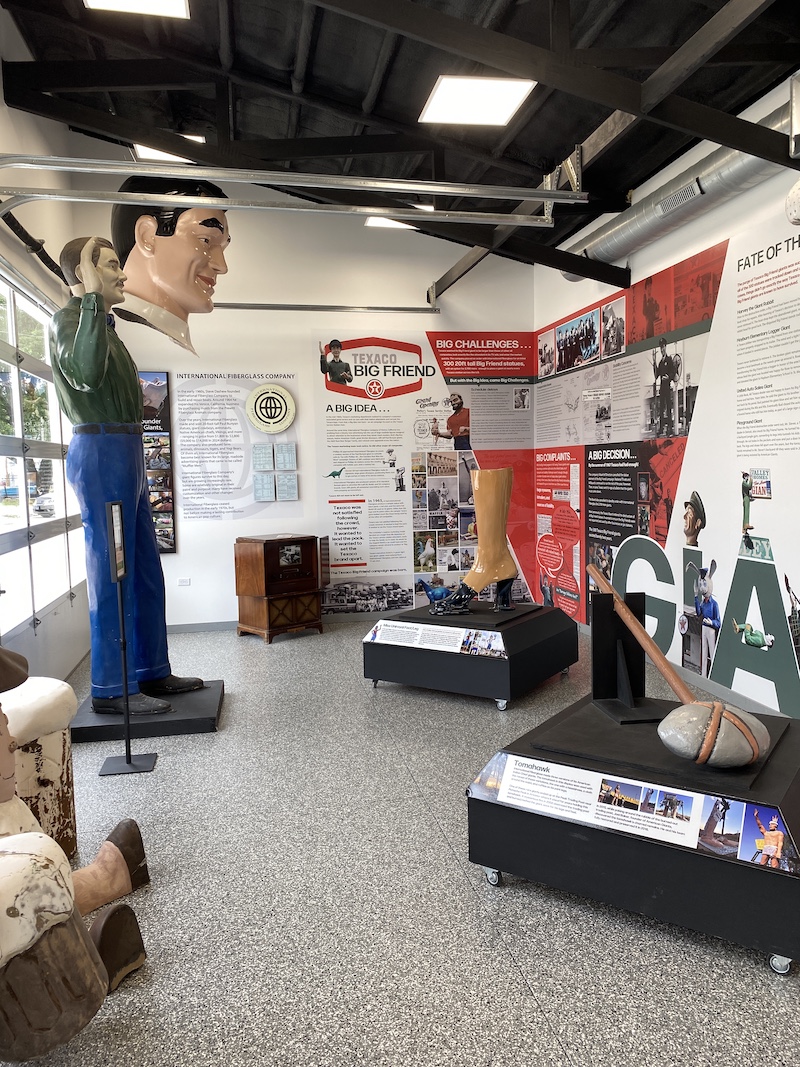

The installation of the giant, a Texaco Big Friend, was the capstone of the grand opening of the American Giants Museum in Atlanta, Ill., in May. The museum is one of the last places you can see the great genre of roadside kitsch: Muffler Men, 20-foot-tall fiberglass figures that loomed over Studebakers and Stingrays in the 1960s and ’70s, demanding the attention of motorists cruising the country’s still-young highways. They stood in front of businesses, arms extended, holding supersized versions of whatever their owner was selling. Often this was mufflers, hence the name by which they’ve come to be known.

The first Man was made by Bobbie Lee Prewitt, a California rodeo cowboy with a side gig making fiberglass cows for steakhouses and dairies. In the early 1960s, Prewitt constructed a giant lumberjack holding an ax for the Paul Bunyan Cafe of Flagstaff, Ariz. The cafe sat on Route 66, and its owners wanted something to lure in passing drivers.

When the cafe erected the statue, it did more than just grab travelers’ attention. It also caught the eye of Steve Dashew, who saw big things in the big man. Dashew bought Prewitt’s business and set about turning the company, International Fiberglass, into the world leader in large men holding things. Recognizing that the market for giant lumberjacks was finite, Dashew diversified. From the basic Muffler Man — a vaguely anonymous beefcake with a jaw that could chew diamonds — he added Stetsons or eye patches and peg legs to produce cowboys and pirates. A different head turned manly Muffler Men into Mortimer Snerds: gap-toothed dopes in straw boaters that were favorites of amusement parks. Arms and accessories could be modified to advertise ice cream, golf clubs and more. (The only Muffler Women International Fiberglass made hawked tires for Uniroyal.)

For a time, Muffler Men were popular advertising tools. They were eye-catching, fun and perfectly suited for the era’s smaller roads, where their presence was unmissable. But the development of the Interstate system proved to be their demise, as motorists bypassed the towns the giants stood in. Barely a decade after Prewitt crafted that first lumberjack, the last one rolled off the assembly line.

In the decades since, Muffler Men have largely disappeared, sent to landfills or left to bleach in the sun on some lonesome two-laner. Today, only a few hundred remain. These colossi of Americana might have disappeared entirely were it not for a small but dedicated group of enthusiasts who have worked to find, document and restore them.

Leading these efforts has been Joel Baker, an audio tech and videographer living in Colorado. Baker’s obsession began in 2011, when he heard about a Muffler Man in Dade City, Fla. “Something clicked in my brain, and it was like, ‘This is what I’m supposed to do,’” he recalls. He began spending hours each week searching for rumored Muffler Men — digging through newspaper archives and social media for clues to their whereabouts and driving around the country to find them, occasionally hiking into the woods or climbing into attics to track down body parts. “It’s hard to be a treasure hunter in 2024,” Baker says. “Everything’s been found. But these giants are still out there.”

Through his sleuthing, Baker has become the country’s foremost authority on Muffler Men, and his work underpins the American Giants Museum. Everything on display, from International Fiberglass pricing documents to the Muffler Men installed outside — at present, the Big Friend and a Snerd, with plans for a Viking, a cowboy, a Native American and a Uniroyal Gal to join them by 2026, Route 66’s centennial — are on loan from Baker’s personal collection.

Baker first arrived in Atlanta, Ill. — population 1,637 — in 2012 to make a video for his website and YouTube channel, American Giants, about a Muffler Man sitting pretty in the middle of town. It had originally stood at a hot dog stand on Route 66 in Cicero, Ill. When the stand closed, in 2002, the Route 66 Association of Illinois sought to find its Muffler Man a new home on the highway. The original Route 66 ran down Arch Street, downtown Atlanta’s main road, so the head of the association’s preservation committee called Bill Thomas of the Atlanta Betterment Fund to ask if the town might adopt him.

“I went down to the then-mayor’s house,” recalls Thomas. “I’ll just never forget — I sat at the kitchen table with him and said, ‘What would you think of a 19-foot-tall statue of a giant holding a hot dog being placed right in downtown Atlanta?’ And to his everlasting credit, he didn’t pause more than two seconds, and he said, ‘I think that sounds like a good idea.’”

Ten years later, Thomas noticed through his office window a guy with a GoPro attached to a boom mike filming the statue’s head. Being the good Midwesterner that he is, Thomas introduced himself. The pair struck up a friendship and eventually got to talking about a museum. On the corner of Arch and Vine streets, the American Giants Museum resembles a vintage Texaco service station, a design that nods to both Atlanta’s Route 66 history and its marquee attraction. Even among the remaining Muffler Men, the Big Friend is a rarity. In International Fiberglass’ heyday, several fuel companies ordered giants and other figures for national advertising campaigns. Phillips 66 commissioned a line of cowboys, Sinclair had dinosaurs made, and Esso ordered tigers. But no company was prepared to take things as far as Texaco, which planned to order 3,000 giants for its Big Friend campaign. Not content with a pre-existing mold, Texaco hired a sculptor to create a custom design. The final model was 25 feet tall, one of the largest International Fiberglass ever made.

The project was a disaster. Beset by delays, logistical problems, and the statues’ tendency to topple in even the slightest breeze, the Big Friends campaign was canceled after only 300 had been produced. Not wanting other companies to repurpose the Big Friends, Texaco ordered them to be destroyed. Only six are known to have survived.

The American Giants Museum Big Friend originally manned a Texaco station next to Caesars Palace, but by the time Baker found him, he was lying in pieces in Pahrump, Nev. There was an enormous gash through his torso, and huge chunks of him were missing. “We were its only chance,” Baker says. He purchased the remains and transported them to Marion, Ill., where some of his partners had a side gig restoring Muffler Men.

Even in the best cases, restoring a Muffler Man can take up to 150 hours. They’re first examined for clues to their history and original form; like medieval manuscripts, many are palimpsests, having been repainted and altered by subsequent owners. Then they’re sanded down to their gelcoat, repaired, painted and reinforced internally. Finally, their head, torso, arms and legs are bolted together. The Big Friend, however, was not a best-case scenario. “He was not friendly to us,” jokes Michael Younkin, Baker’s partner and the owner of the Marion restoration shop, now known as (Re)Giant. Younkin and his team had to patch the Big Friend’s damaged torso and craft entirely new arms.

The effort was worth it. “There’s nothing like going down the road with a brand-new giant and seeing people pointing and taking pictures,” says Younkin. “Being able to save a piece of history — that’s a big deal for us.” At the end of the Big Friend’s 2,000-mile journey — from Las Vegas to Pahrump, Marion and, finally, Atlanta — Younkin manned the forklift that set him down in his new home. The red stars on his dark green hat and uniform had a polished sheen, and his piercing blue eyes seemed to shine. Since the Big Friends were manufactured in 1967, he was the only one to be restored to his original condition.

For Baker, salvaging these giants is all about the difference they make to our road trips and roadsides. “When people go and they take a minute to stand with or take pictures of a Muffler Man, for a few seconds you can step out of the mess we live in — daily life, the news and all that — and just enjoy something very simple that’s larger than life.” But it’s not just those few seconds. Making the search for Muffler Men part of a road trip doesn’t just offer the goofy thrill of finding these relics in the wild; it’s also an excuse to get off the freeway and onto the smaller streets where America is most interesting.

While Muffler Men are scattered across the country, Baker feels that now, as then, the best road trip for giant-spotting is a spin down Route 66. The hunt entails a good deal of getting out of your car to gawk, so fall is an ideal time to tackle it, letting you avoid Midwestern winters and Southern summers.

On the road, there are giants to discover even before you leave Chicagoland. In the suburbs of Berwyn and Burbank, you’ll find a new Muffler Man smoking a cigar while holding a chicken wing and hot sauce on the roof of Cigars & Stripes BBQ Lounge, and a battle-ax-wielding Frankenstein’s monster in a purple suit at Haunted Trails entertainment center. There are classic Muffler Men like Atlanta’s hot dog giant and a cowboy overlooking a used car lot in Gallup, N.M., but the highway is also home to more exotic specimens. Clutching a shiny silver rocket, Buck Atom of Buck Atom’s Cosmic Curios on 66, just outside downtown Tulsa, is a literal space cowboy. At the end of the road, Los Angeles’ Chicken Boy has the body of a man and the head of a bird. Once the mascot of a fried chicken joint, he’s become a local celebrity, gracing T-shirts, skateboards and other merch.

Of all the Muffler Men along the highway, however, the one that’s most impressive is also one of the most basic. With so many giants having disappeared, it’s remarkable that Bobbie Lee Prewitt’s original creation is likely still standing, barely a mile from its first home. Though its identity hasn’t been proven definitively, it’s thought that the Paul Bunyan Cafe statue is still in Flagstaff, where it now serves as a mascot on the campus of the Northern Arizona University Lumberjacks.