For 30 years, the Crocodile Cafe has embodied the sound and spirit of Seattle. Perched at the corner of Second Avenue and Blanchard Street in the city’s Belltown neighborhood, the venue opened in 1991 and from day one served as a no-frills hangout for the city’s thriving local music scene through the grunge explosion and beyond. Nirvana opened for Mudhoney there in 1992 under the fake name Pen Cap Chew; tickets were a whopping three dollars. R.E.M. guitarist Peter Buck was a constant presence at the Crocodile after moving to Seattle in 1993, while once-local acts such as Sunny Day Real Estate, Death Cab For Cutie, Sleater-Kinney, Modest Mouse, Fleet Foxes and Macklemore all cut their teeth in the club before achieving international notoriety. The Crocodile shuttered in 2007 due to long-standing financial issues, but reopened two years later following an extensive remodel. In this exclusive oral history, Fifty Grande explores the most memorable moments of the storied venue’s history with longtime Seattle musicians, journalists and fixtures of the scene.

In the beginning…

Jerry Everard (Crocodile Cafe co-founder):

Stephanie Dorgan [co-founder] and I were young lawyers at a big downtown firm. I guess I had enough ignorance and chutzpah that I could do something different. At the time, all the rooms in Seattle were called “holes with poles.” Basically, you couldn’t do a show in a room that served alcohol. It had to be in a pub. All these pubs tended to be long, narrow places with a bar. There’d be a pole and you’d throw a stage up at the end, and that’s where bands would perform. That was fine, but at the same time, in the late ’80s, people started saying, “Well, why can’t we have real venues in Seattle? Why can’t we have a place where you can have a drink, and more space?” The papers would say it was because of the liquor licensing and insurance requirements. I looked at that and thought, “I’m a lawyer. I can figure that out. We can do this.”

Stephanie and I were both single and running around Seattle, and we were intrigued with her sister Constance’s scene at the time. We’d follow her around to all the shows she was going to, and we were fascinated. I discovered that you could do live performances if you had a banquet room in a restaurant, so we started looking around and found this place in Belltown, which at one time was licensed as a restaurant with a banquet room. They were doing belly dancing in there. We had a crazy lease negotiation with Howard Close, who is still alive, by the way, and still owns the building. He’s an interesting guy. He served us coffee out of mugs made from tin cans with the lid taken off and soldered into a handle. He was extremely frugal — a real Depression-era sort of mentality. But he liked us, so he leased us the space.

We were really flying by the seats of our pants. We didn’t know anything about restaurants or how to run a business. We met Craig Graham — Graham Graham is his name now. He was doing the art installation at the law firm and was like, “I’m all in on this. I’ll join you guys and help you build this out.” He and I spent a year building out the space and cutting lines in the floor to create the cool patterns. His aesthetic was built into the place and created that really great ambience. It became a real labor of love. It finally opened a year and a half after we started building it (laughs). When we opened, we were able to serve alcohol. You could get a drink and see a show. The room was probably one of the better laid-out rooms at the time, even though it still had a post you had to work around.

Scott McCaughey (musician, the Young Fresh Fellows/the Minus 5/R.E.M.; talent booker):

Terry Lee Hale was the first booker. I took over for him in September or October of ’93. I stayed there through the end of ’94. So, it was a relatively short period — a little over a year. But a lot changed at that time because the Crocodile was doing a lot of local nights when I started working there. It started to shift into getting a national reputation, and we started getting a lot of touring bands coming through. That really, really changed things. It was quite interesting for me to be on the other side of the equation — being the guy who is paying the bands instead of the guy who is in the band, praying that we’d get paid and and hoping that we might get some beer on the rider (laughs).

Val Kiossovski (bar manager):

I worked at the Off Ramp for five years. The Croc was the new kid on the block, and the cool one. I remember one night I was dating a girl and almost dirty danced over there. I don’t remember to what music. We were just drunk. That was my first experience with it. I would just pop into Belltown over the next four years, so I didn’t have much of an idea of what was going on over there. The RKCNDY and Off Ramp scene was different. A lot of people definitely equate the Croc with the grunge era, because some of the main players and the most successful bands performed there. But actually, for me, grunge always will be connected with the Off Ramp and RKCNDY more than anything, and the madness of the scene at that time.

“It was pretty exciting. Just about anyone you can think of passed through there.“

Val Kiossovski

When the Off Ramp closed, I spent a couple months languishing at this fisherman bar, because I had to pay the bills. I heard Hamish Todd was looking for a seasoned bartender, so I said, “Man, I’m dying here.” Eventually Stephanie offered me the bar manager position. So for the next nine years, I ran the bar there, up until 2006. For the first four or five years, it was a never-ending roller-coaster of the best the scene can offer. It was pretty exciting. Just about anyone you can think of passed through there.

Jerry Everard:

I’m going to say we paid about 4,000 (dollars) a month. Every month we’d have to figure out how to pay the rent, and we’d have two pennies left on the table: one for Stephanie and one for me. Graham’s not getting anything, and neither are the investors. Belltown at the time was pretty earthy and grimy — not shiny like it is now. It was gritty, and that was part of the appeal at the time for us.

THE OPENING DAYS

With a listed capacity of 381, the Crocodile officially opens on April 30, 1991, with performances by area bands Love Battery and the Posies. Less than six months later, the Seattle music scene — and the state of rock ’n’ roll worldwide — would be forever changed by the release of Pearl Jam’s “Ten” and Nirvana’s “Nevermind.”

Jerry Everard:

I don’t remember anything about the show itself, honestly. I was more worried about the operations and trying to get the bar organized. I think we got our delivery just as the doors were opening, so I was trying to work with the bar managers to set up the bar and get drinks out. Was security actually checking IDs? It’s absolutely a blur. I couldn’t believe we got through it. Nothing terrible happened (laughs).

Ken Stringfellow (musician, the Posies):

In my memory, I think that we already knew Stephanie Dorgan. I think she’d already talked to us about it when things were conceptualizing. That’s how we wound up playing that opening night. At that point, we could have played a much bigger venue. We were usually playing the Moore Theatre, which can hold 1,800 people. But we opened the show, so we were the first band to play. I can picture little flashes of it. We were touring like crazy at that time. Even though our album came out in 1990 and we’d done a bunch of touring. In ’91 we did a U.S. tour with the Replacements, a West Coast tour with the Dharma Bums and then a whole other headlining tour after that. So [opening night] was just stuffed into a little mini-break between those legs. I’m pretty sure in some ways we were on fire but also a little bit burnt. We were pretty excited about the idea of being a part of something new. We liked Love Battery a lot. It was exciting to get to know them as pals. We were kind of popular, so I guess that’s why we were asked to do it. I think they just wanted to kick things off with a bang.

“We were pretty excited about the idea of being a part of something new.”

Ken Stringfellow

Jerry Everard:

Looking back at it, it really was driven by excitement. It wasn’t the idea that there was something that was going to blow up and become big. I remember lines of people coming down from Capitol Hill to go to shows downtown, and then walking back at night. I guess if I would have stopped and thought about it at the time, I would have realized something was going on here. But it was more like, “This is really exciting and I want to be a part of it. This is a great community.” That’s what drew me in: being part of this group of people making music that I liked. The music connected with me, and they were people who were interesting to me. They became friends. It’s a lot more organic than the idea of, “Oh, this is something we’re going to hype up.”

SMELLS LIKE GRUNGE — THE CROCODILE IN THE ’90s

Jerry Everard:

Stephanie and I were both lawyers, and we knew one of us would have to stay on and have a day job. So we flipped a coin, and I lost. If it had gone the other way, the place probably would have been a dismal failure. It worked out for the best, because it really played to both of our strengths. Maybe there was some divine intervention there. The result was that I’d spend all day at the law firm, change out of my suit in the office upstairs and, more often than not, go to the Croc and get behind the bar. I had them train me how to be a bartender and work in the kitchen — anything to keep the labor costs down. We were struggling every month to pay Howard his rent and keep the thing afloat. Anything I could do myself, I would do. I’d always work Saturdays — I’d start in the day and work as late as I could into the night. Often, bands would come hang around on Saturday afternoons or take a break from band practice nearby.

Ken Stringfellow:

I wouldn’t be surprised if I spent 500 or 600 nights in the Crocodile in my life. Maybe more. It cannot be underestimated how much time I spent in that place. Scott McCaughey is such a pivotal figure for us, not only because we admired him as a musician but because he’s the guy that gave the Posies our first gig in 1988. In April of ’91, Alice in Chains had already come out. Soundgarden had come out. People thought things had gotten so huge, but they had no idea what was around the corner was going to be even bigger. It already seemed pretty out of control in 1990. Since we didn’t share the perception of what the rest of the world thought Seattle was like, we didn’t need a refuge. So the Croc was just a hangout. It was our HQ. And for me, it was free to get in. I don’t think I ever paid for a show (laughs). By playing that opening night as a big underplay for us, we got paid back in admission from that point on.

“Kurt Cobain loved our pinball machine.”

Jerry Everard

Jerry Everard:

Kurt Cobain loved our pinball machine. He started hanging out there a lot, especially on Saturdays. You could see that there were connections being made between all these different people thanks to the Crocodile. I didn’t get to see much of the show when Nirvana opened for Mudhoney as a surprise, to be honest with you. I’d go in the back from the kitchen and hang out at the soundboard with Jim Anderson, our sound man, and watch a few songs. The bigger memory for me with Nirvana was when they played on “Saturday Night Live” in January of ’92. TVs were like boxes back then, with tubes. I got one and set it up at the end of the bar. Everybody that knew them came and crowded around and watched the show. I gave everyone drinks and it felt like the pinnacle at the time. And then Kurt smashed the drum kit up. I got caught up in the moment and I took the TV and shoved it off the end of the bar, and it crashed on the floor. Everybody went crazy. That’s my biggest memory of a Nirvana show (laughs).

Nils Bernstein (publicist, Sub Pop Records):

The show that is memorable for me is the second-ever Sunny Day Real Estate show. [Label co-founder] Jonathan [Poneman] wanted to go see this band, and I was like, “Okay, whatever.” They opened for someone and went on at 7 p.m. There were maybe 10 people in the audience. Anyone else who says they were there was not there (laughs). I think all their friends were underage. It was literally like watching U2 in 1980 and was one of the five best shows I’ve ever seen in my entire life. Imagine that first record being played exactly like it sounds on the record, except more intense and emotional. We signed them instantly, or at least told them that we would. It wasn’t a showcase per se, but we might not have even bothered to go if it wasn’t at the Crocodile.

“It was literally like watching U2 in 1980 and was one of the five best shows I’ve ever seen in my entire life.”

Nils Bernstein on Sunny Day Real Estate’s second-ever show

Dan Hoerner (guitarist, Sunny Day Real Estate):

I remember clear as day looking out into the audience and seeing Poneman and this guy Dave Rosencrans, this long-haired Sub Pop dude. We were playing “Song About An Angel” and me and [frontman] Jeremy [Enigk] exchanged this look. I looked and this guy Dave just had tears streaming down his face. That was the thing we were going for — that was it for us.

Scott McCaughey:

So many of my favorite shows have been at the Crocodile, not only before and while I worked there, but after. It was just a great place to see and hear music — especially to hear music. Jim Anderson had that room so dialed in. It just sounded like a rock club should sound. It wasn’t big enough to get echo-y. It was small enough to have a tight, focused sound. When it was super packed, it could be pretty uncomfortable.

Nabil Ayers (co-founder, Sonic Boom Records):

Me and pretty much everyone I knew moved to Seattle in the summer of ’93. I remember figuring out which clubs sold which kind of beer. The Croc sold Sierra Nevada bottles, so we’d buy them, keep them in the car and then smuggle them in. We’d see Flop and the Young Fresh Fellows and the Posies there. They were local and were getting signed to major labels, but I thought they were so distant from Soundgarden, Nirvana and Mudhoney. In my head, it was not part of grunge. Nirvana didn’t start there, because they couldn’t have. To me, it was detached from that history. I thought of it as a bit more intellectual — not high-brow, but smarter and more adult.

Michael Lee (bar manager):

People always talk about the pillar in the showroom. It was really fucking annoying in real time. It was a vision obstruction. I guess you could lean against it, but I don’t know how this has gotten so much lore. It was not a positive quality.

Jerry Everard:

There were a lot of people connected with some social service agencies in the neighborhood, and a fair homeless population. One night right after the main dinner rush, two guys on the street were fighting outside the place. Back then, the Croc had giant glass windows all the way around the outside. One guy threw the other into the window, and a piece of the glass, which wasn’t laminated at all, came down like a guillotine and cut into his neck. Clearly it hit an artery, because he was spurting everywhere. We called the police right away, but both of them freaked out and ran down the street as fast as they could, even though one of them was gushing blood. The police said they followed the blood, but they couldn’t find the guy. We realized the windows could be dangerous, but before that, I had no idea what the potential risks were. If I had, I probably would have never, ever gone into it.

Scott McCaughey:

When I booked the Presidents of the United States of America, they had a different name up to that point. They were local guys, so I thought, “These guys are pretty cool. I’m going to book them.” They had apparently been building up a little bit of a following already just by playing live, and they changed their name to the Presidents of the United States of America right before the show I had them do. I was like, “I guess I’ll give them a Thursday night or whatever.” The place was crawling with people who were singing along with songs already, before the record even came out. I was like, “Oh, man — I really stumbled on something here. These guys are definitely going somewhere.” They were so great live early on — just so infectious.

“The place was crawling with people who were singing along with songs already, before the record even came out. I was like, ‘Oh, man — I really stumbled on something here.'”

Scott McCaughey on booking local band

the Presidents of the United States of America

Nils Bernstein:

The Frogs played once, and Eddie Vedder was filming it. He gave me the camera for a minute and was like, “Do you mind filming until I get back?” It was so funny. The Frogs, and Eddie Vedder is filming it, but now I have his camera and am onstage? Nobody gave a shit. It was half full that night. There’s nothing really memorable about it other than, even in the moment, this is probably something people would like: Eddie Vedder, fully in the mix, filming the Frogs and being passionate. It was such an everyday occurrence that it was kind of funny.

Scott McCaughey:

The first Guided By Voices show there was something I booked. I really went out on a limb because I had to lay out a thousand-dollars guarantee. That was a really big risk for me, because we were tight with money and didn’t like guarantees. I really wanted to see them, so I just decided to give them the thousand dollars. I said that to me — I didn’t say that to Stephanie (laughs). We did lose money, because I think only 100 people came. But oh, man. Cobra Verde and Prisonshake also played. When Guided By Voices got up there, it was just mind-blowing. The 100 people who were there will never forget that show and, of course, every time they came back, it was just packed through the roof. That was just one of my favorite shows ever.

Nabil Ayers:

Rocket from the Crypt was the best show I ever saw there. It was just fucking incredible. Same with Sleater-Kinney when “Dig Me Out” came out. The Strokes played their first Seattle shows there too. You’d get to know the door guys and they’d just walk you in. You’d end up in the back bar and when they’d kick everyone out at 2 a.m., you’d stay back there until suddenly it was 5. It was really fun.

Hannah Levin (journalist, Seattle Weekly/the Stranger; DJ, KEXP):

The booker, Christine Wood, was an extremely valuable part of making the Crocodile a good place for discovery. She had very good taste, but it was very diverse. She knew she needed to make smart booking decisions to keep the doors open. The Cherry Poppin’ Daddies probably weren’t her favorite band, but she booked them because the bar would sell a bunch of booze. That meant that on a Tuesday night, she could take a chance on a scrappy little punk band called Sleater-Kinney. People often talk about the role of a venue in the ecosystem and the health of the music community, and I think that was a very valuable thing that she did by making space for bands at all stages of their career.

Nils Bernstein:

The Sub Pop fifth anniversary party was scheduled for the day after Kurt died. We thought we should do it somewhere bigger, but we knew it wouldn’t be as fun. It became a wake. It was Velocity Girl headlining. Everyone was just drunk, freaked out and emotional. Sarah from Velocity Girl ran off stage crying when they started playing. It really was bananas. God, it was so weird. We had made fortune cookies with funny sayings in them as party favors. One was like, “Kurt just farted,” so we had to get rid of the fortune cookies. We were kids trying to convert this party into this respectful wake that nobody really wanted to be at, but everybody wanted to be together. We couldn’t just cancel it because it was therapeutic in a way. Again, we did it at the Croc in the first place even though it was too small. It was easy to turn something intense like that into a party, or an intimate thing. It felt OK to have it there, because it was manageable and it was people we knew and cared about. You weren’t arguing with the security people about something.

Susan Silver (manager, Alice in Chains/Soundgarden):

Mad Season was something that Layne Staley wanted to be really separate from Alice In Chains. They played their first show at the Crocodile, and Layne was in his time of exploration at that point. The pressure of success can be a really confusing and sometimes toxic environment, so that was his way of expressing that.

Ken Stringfellow:

Those guys were all from big bands — not just Layne, but Mike from Pearl Jam and Barrett from Screaming Trees. That was pretty intense to see in that venue.

“‘Dude, that’s Joey Ramone.’ ‘Bullshit — where?’ ‘Right fucking there. Right there, talking to Eddie Vedder.’ That to me was the quintessential Seattle moment: two guys being more taken aback by the presence of Joey Ramone than they were of Eddie Vedder.”

Nabil Ayers

Nabil Ayers:

The Ramones headlined Bumbershoot in September of ’95. Before the festival, there would always be secret shows at the Crocodile with some of the bigger bands from the festival. I was down there, and Live was playing. At first, I was like, “Who fucking cares about Live,” but they were really good. I go back into the bar, and I overhear these dudes next to me saying, “Dude, that’s Joey Ramone.” “Bullshit — where?” “Right fucking there. Right there, talking to Eddie Vedder.” That to me was the quintessential Seattle moment: two guys being more taken aback by the presence of Joey Ramone than they were of Eddie Vedder. The thing was, the Pearl Jam and Soundgarden guys, and some of the Alice in Chains and Mudhoney guys, they were everywhere. They went to shows. I never saw them get bothered. They were just people at the bar, and they were treated as such.

Jerry Everard:

For Stephanie and I, our vision of what we wanted to do there diverged at a certain point. She was really focused on personal relationships with folks and really pushing hard in that direction, and I wanted it to be just the best venue for musicians. All musicians — not just stars or that sort of thing. So, we had sort of a different vision about how to keep moving forward. We had some financial issues, and I don’t really want to talk too much about it, other than to say, I ended up in a lawsuit with her. It was way easier for me to say, this is yours. You make it your legacy. I’m going to take everything I’ve learned and make a club from scratch that has all these things I wish we had there. We didn’t have green rooms at the Croc because we never thought about that when we were building the place. When I opened Moe’s in January of ’94, we had elaborate green rooms, with showers for touring bands. I learned how people interact in a gathering place, and designed the new place around that. I used the split as an opportunity, rather than something to be angry and pissy about. That’s the way I left it.

A HOME AWAY FROM HOME

Jerry Everard:

In the early days, whoever we got to cook at the time, the menu would be driven by whatever they felt they could cook. Honestly, we didn’t care about the food (laughs). That was a necessary evil to allow us to be able to have a liquor license and do the shows. The space requirement that we had to dedicate to the restaurant was always a drag on business for us, but we tried to do the best we could with it.

Nils Bernstein:

The bar was not just separate from the music room, but it was physically far away. It amounted to two clubs in one, so it could accommodate more people than the capacity of the venue. You could spend the whole night just in the bar if you weren’t that into the bands for whatever reason, or you could spend the whole night in the club. If you had enough drinks, you didn’t need to go back to the bar. It was a social hub. People went to shows for social reasons anyways, but with the Croc, you’d go even if you didn’t give a shit about who was playing. They had very generous pours (laughs) and very respectable bartenders, as opposed to clubs where the drinks are overpriced and no good. There were so many opportunities for everyone to interact. It wasn’t a club that had these delineated areas for the bands and then everyone else. Everybody was in the mix together. That made a huge difference on the vibe. It was collegial.

“That was one of the greatest things about it. It had these separate spaces where you could have distinct experiences.”

Susan Silver

Susan Silver:

There was something about the sensation when you walked into the showroom that was distinct. The bar was its own world, transporting you to another whole scene. That was one of the greatest things about it. It had these separate spaces where you could have distinct experiences. You’d end up in the restaurant space at the end of the night having some unhealthy meal to get you home. It was more about the crush of people trying to see around each other and the pole, and the heads of the musicians on the very low stage, and always waving at Jim the sound guy. It was a party atmosphere and an eclectic environment. There was nothing uptight about the Crocodile.

Hannah Levin:

I grew up in Tacoma and moved to Seattle at a really good time — a week before I turned 21 in 1991, the week before “Nevermind” came out. I spent a lot of time at the Off Ramp, which was pretty dirty and rough and tumble. The Crocodile was a lot more warm right off the bat. The first thing I did almost every single time was hug Kevin, the door guy. I’d take a peek at the set times, which were almost always 10, 11 and 12. I’d go to the back bar and get my vodka-and-cranberry from Val, and say hi to Jim Anderson, who was always so sweet to me as I was figuring out what I wanted to do in the music business.

Val Kiossovski:

That was one thing the Croc provided that virtually no other club in town had. The way Stephanie conceptualized it was virtually three different venues wrapped in one. It was unusual, but it was the right thing for the right time and the right place.

Nils Bernstein:

Why did the big bands play there? Capacity was so minimal. How did it make sense to play such a small room? Well, they were paid well, or they did multiple sets. The room was more horizontal, so you had actually had really good sight lines from everywhere. Even when it was packed, it still felt really intimate. It played into this idea that there was no separation between the audience and the band. Seattle became a place where it was all VIPs. Everyone was famous. But it wasn’t about that at the Croc.

Scott McCaughey:

It was a great breakfast place too. If you went on a weekend, you’d always see people from bands there hanging out. The bar in the back is always where you’d see people. We figured out a way to open up the room into the cafe, which expanded the capacity a little bit. I think the legal capacity was 380 (laughs), and we usually had 500 or 600 people in there. We could have gotten busted at any moment by the fire department. There was no backstage really. There was no real privacy or protection from someone busting in and saying, “Heyyyyy, man! Peter Buck!” Bands would be like, “What do you mean, you don’t have a dressing room?” They’d put batteries and socks on the rider and we’d be like, “Yeah, no, that’s not going to happen” (laughs).

Michael Lee:

The size of the showroom made the Croc special. There’s the removable wall, so you’d have that intact for a local show on a Tuesday, and when the Strokes played that weekend, you take it out. That modular quality was very handy. Just knowing the place had been there since ’91 — it opened right in front of the grunge wave. There’s history in the bones of the building. Also, lots of the staff were playing music and trying to create their own success. There was a lot of really positive co-hype. It was always competitive, but it was more supportive and uplifting rather than trying to muscle your coworker’s band off a bill.

Hannah Levin:

At the end of the night, after the last band had finished, Jim would turn on the lights and play the Billie Holiday song “I’ll Be Seeing You.” It was such a beautiful, sweet, loving ritual. Sometimes the lights would go on and Doug Martsch from Built to Spill would go up and do another 20-minute solo, but when “I’ll Be Seeing You” started playing, you knew it was time to put your cocktail glass down, say goodbye to Kevin and make your way to the door.

SHINY HAPPY PETER — A SUPERSTAR ARRIVES

Scott McCaughey:

When Peter Buck came to town in ’92, he was working there for a month on the R.E.M. album “Automatic for the People.” They were mixing the record there, because R.E.M. likes to go to different places and experience different cities. They thought, “h, let’s mix in Seattle.” He called me when he arrived, because I knew him a little bit from Athens and through other friends. We met downtown and had a bunch of margaritas and some Mexican food. We were walking back to the studio afterwards and we walked by the Crocodile. I saw Stephanie standing out front and said, “ey, Stephanie, how’s it going? Let me introduce my friend Peter.” I guess that sort of started it all off (laughs). We would hang out a lot because the studio was right down by the Crocodile, so we’d go over there and catch bands while he was in town. He and Stephanie started seeing each other, so then he started spending a lot of time in Seattle. Eventually, he became a citizen of Seattle, got married to Stephanie and had kids and all that stuff. I became part of the R.E.M. live band — that was why I left at the end of ’94, because we were starting the world tour. That’s when I handed it off to Christine Wood. She was very capable.

Peter Buck (guitarist, R.E.M.):

I moved from Athens, Ga., to Seattle in 1993 and started crossing paths with the Pearl Jam and Nirvana guys. Actually, I was Kurt’s next-door neighbor. He used to call occasionally, just to talk about stuff. But it was so overwhelming. The Athens scene is so laid-back. Even when R.E.M. got popular, it wasn’t that big of a deal. In Seattle, it was heavy duty. All of a sudden, these guys I’d vaguely met were as famous as Elizabeth Taylor. It was really hard for everybody to deal with. Every night at the Crocodile, there’d be thousands of kids who you could tell hadn’t heard a hard rock record until the year before. I remember thinking, “I don’t know how these guys are dealing with it.”

Nils Bernstein:

Normally at a show, you wouldn’t see Nirvana, J Mascis and Peter Buck just sitting around. But at the Croc, they’d be the first people you saw when you walked in.

Scott McCaughey:

Peter was there to help. He wasn’t really involved in the club at all, but he’d say, “Oh, I’ve got these friends coming through. Can you get them a night?” We’d play a lot too with our band the Minus 5. We’d do benefits and put bands together. It probably lifted up the reputation of the club a bit, but the club was already a pretty happening concern before then. The scene was exploding.

Nabil Ayers:

Peter used to come into Sonic Boom fairly often. We were almost a bit nervous not to bother him. One night, I was peeing at the Crocodile, and I hear this voice next to me saying, “Hey, man, I really like your record store.” I look over, and it’s Peter Buck taking a piss. Then it was like, “Okay, now we’re cool. We’ve had a conversation at a urinal.”

Scott McCaughey:

At some point later, Patti Smith was coming through to do a reading. It was probably a benefit for something. Peter and I said, “You know, hey, Patti — Peter and I could put a band together and back you guys on a couple of songs if you want.” She and [guitarist] Lenny Kaye and her daughter were there. She said, “Yeah, well, maybe we could do a song or two.” She came to soundcheck and we had learned like 10 of her songs — most of “Horses” and couple others. We soundchecked one song and she said, “Wow, this is like having my own little garage band here.” We played pretty much the whole set with her, and it was a total mind-blower. It was one of the greatest nights ever.

Hannah Levin:

Even in the ’90s, there were lookie-loos aplenty. I definitely remember one night that Kevin Costner walked in with two blonde L.A. models, and we were all like, get out of here, dude. Generally speaking, that was frowned upon. When you don’t have an atmosphere like that, people feel more comfortable just letting random things happen, like pulling Patti Smith up on the stage with you.

Scott McCaughey:

R.E.M. was recording a song for a movie at Bad Animals studio right downtown, on the same night in ’96 that Yoko Ono was playing at the Croc. Yoko asked if they wanted to come play on a song, and Peter wasn’t really interested in it for some reason. I’m not sure why. But [R.E.M. bassist] Mike Mills and I were like, “Hell yeah!” So we joined her for “Mind Train,” with Mike on organ and me on piano. I took a super crazy piano solo and Yoko looked up at me as if to say, “That was pretty cool” (laughs). We went out to dinner with them afterwards and it was just amazing. It was one of the greatest moments of my life to get up and play with her.

Val Kiossovski:

I have very fond memories of Peter. He’s always been very gracious. I like his style and the way he treated everyone. He’s a good man.

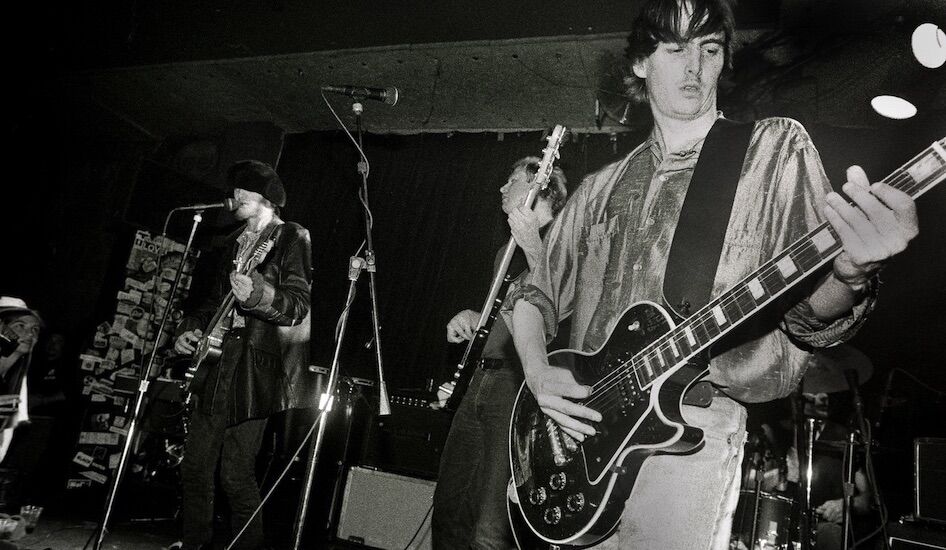

Photo by Shutterstock.

Ken Stringfellow:

Scott introduced Peter and Stephanie and then they got married. Hanging out at the Crocodile in many ways led to me playing in R.E.M., because all those initial conversations with Peter stemmed from both of us being there every night. If the Posies were still active in 1998 — we had disbanded — I never would have ended up playing in R.E.M. They had their own internal rule that they wouldn’t poach somebody from another band that was active because, you know, how could anyone say no to playing in a band of that stature? It would potentially damage an active band if you had to make that Sophie’s Choice. That wasn’t the case in 1998 for me. My band had disbanded and my songwriting partner had quit, so I was a free agent, and off I went.

Scott McCaughey:

R.E.M. finally played at the Crocodile in 2001, which was pretty nuts. I feel like some version of the Minus 5 might have opened that show, or maybe we were the billed act. Mike Mills and I did some acoustic songs and then it turned into a full R.E.M. show, with Eddie Vedder guesting.

Peter Buck:

We were all just having fun and taking requests. We even did [the Pearl Jam song] “Better Man,” which none of us had ever rehearsed. We got, like, 90% through it. Ed said, “Do ‘Begin the Begin,’” and [R.E.M. vocalist] Michael [Stipe] said, “Okay, if you sing it!” Those chords don’t go where you expect them to go. We were all looking at each other like, “What the fuck? How does this go?” But Ed knew it.

THEY WANT YOU TO WANT THEM — CHEAP TRICK BRINGS OUT THE BIG GUNS

Val Kiossovski:

My absolute favorite show at the Crocodile was Pearl Jam opening for Cheap Trick as a surprise in October of ’98. Pearl Jam’s performance that night is the best show I’ve ever seen from them. It was absolutely unbelievable. It was the right venue for it and the right circumstances. I saw Pearl Jam at the Off Ramp when “Ten” got released, for a dollar or something. Eddie is one of the nicest people I’ve known.

Scott McCaughey:

It was a three-night stand where Cheap Trick played each of their first three albums in full — a different one every night. My band the Young Fresh Fellows opened the first night, Supersuckers opened the second one and then Pearl Jam opened the third. That was incredible. It was before bands were starting to play an album each night, and Cheap Trick hadn’t been seen in a small club like that for a long time.

Ken Stringfellow:

Only at the Crocodile could you see three nights of Cheap Trick where they did a different album each night. I saw all three, of course.

Mike McCready (guitarist, Pearl Jam):

Getting to play with Cheap Trick was a dream come true. I have been influenced by [Cheap Trick guitarist] Rick Nielsen, who is super important. I throw too many picks out because of him.

TEENAGE WASTELAND — THE BATTLE FOR ALL-AGES SHOWS

Jerry Everard:

We were not permitted to have all-ages shows when we first opened. Underage people could be in the restaurant, but the showroom was completely separate. They could be in the banquet room, but not with the “added activity” license. The city gave us that permit, to allow us to do the shows in the banquet room. The Teen Dance Ordinance was going on then, which basically made it impossible for underage kids to be in the venue. Seattle had a big backlash against what was happening around the mixing of teens and adults at shows.

Robin Pecknold (frontman, Fleet Foxes):

We played there when we were underage, opening for bands. We’d have the “X”s on our hands in Sharpie to make sure we wouldn’t be served alcohol. Sometimes we’d be playing a 21-plus show and we wouldn’t be able to stay before or after.

Michael Lee:

We definitely did all-ages shows in the 2000s, but it was the sort of messy pivot before the Teen Dance Ordinance finally got repealed in 2002. The all-ages shows couldn’t interfere with the evening’s revenue, so they’d often be on Sunday afternoons. It was kind of Wild West-y in how they’d create the environment to do that. You know those big orange netting gates they use for construction? That’s how they created the fault line. It was optically hideous. I never felt like those shows were super successful, but what the Croc did set the template for how other people started to approach doing all-ages shows at mid-sized venues in town. Two years later, Neumos was doing them all the time, so surely it was profitable.

RIDING THE WAVE — FROM ’90s GRUNGE TO ’00s INDIE ROCK GLORY

Hannah Levin:

I put on a Velvet Underground tribute night show in 2000, which was a benefit for the needle exchange program in the district. I thought that was terribly funny. I got permission from Christine to cover the pillar with aluminum foil to make it look like Andy Warhol’s Factory. What a nerd I was. I posted on a bunch of Velvet Underground fan message boards that I was doing this event. One day, I got a phone call from someone that said, “hi, I’m Doug Yule’s manager.’ Unbeknownst to me, Doug was living in a suburb of Seattle and working as a cabinet maker. He’d heard about this tribute night and wanted to participate. The manager was like, “Doug hasn’t played music for years, but he got very excited about what you were doing, and he wonders if he could play and would you help him put together his backing band.” So I then had the distinct honor of assembling a collection of musicians for an actual former member of the Velvet Underground. The violin player I got, Seth Warren, ended up falling in love with Doug’s daughter that night and they later got married.

Robin Pecknold:

The Crocodile was the promised land. It was the best venue in town. It felt like the place you could eventually be headlining just as a local artist. There was Neumos, but I think only a few Seattle bands headlined there. So the Croc was the place. You’d go from Chop Suey to the Crocodile. I went to a ton of shows there — a secret Strokes show on “First Impressions of Earth,” in maybe 2004 or 2005. We were in the front row, me and [Fleet Foxes guitarist] Skyler [Skjelset]. By then, they were doing a lot of all-ages shows, so we were there a lot meeting people. I remember meeting Casey from Fleet Foxes there. I met Dave Bazan from Pedro the Lion and Damien Jurado.

Jerry Everard:

I would not have had a problem going to a show there in that era. I wouldn’t have wanted to run into Stephanie, because tensions for a long time were pretty pretty high. I don’t think she was happy with the fact that Graham and the primary investor in the Crocodile left with me to open our new place. We were flat-out competing. At that point though, I also gave up my day job and was living in the basement of the club. It was my life, 24/7. I didn’t get out to shows that much (laughs).

Robin Pecknold:

The Crocodile was only a couple blocks from a practice place we had at the Institution on Western. Often we’d practice and then go there to do a show. My sister Aja would sell screen-printed demos of ours. We brought 40 in for a show there in 2006 and they all sold out.

Michael Lee:

I worked there from 2001-2008. I missed the initial grunge wave, but that was when Christine Wood was the booker and Frank Nieto was her assistant. I was stunned, because to me, the Crocodile was, like, untouchable. I was really nervous when I started. I was 21, you know? I felt like I didn’t have a right to be there. The Franz Ferdinand show was when I realized kind of what the deal was. You’re Franz Ferdinand, but you still stopped at the Crocodile to almost kiss the ring and sell out this 450-capacity room? I would see that time and time again. It happened with Elbow too. It was fucking insane. They went down Second Avenue with a camera, and they had a screen in the room so you could watch them arrive. I just remember that blowing my 22-year-old mind.

Val Kiossovski:

We had some rough nights. We had a gigantic brawl at an Everlast show. Around the encore, some asshole kicked the intake of water to one of the toilets in the men’s room. It was like a rainforest in there. We had to shut off the water, which meant we had to shut down the show. The whole crowd wound up on Blanchard, and I don’t know what the hell happened, but a huge brawl started. Fifteen minutes of complete mayhem. As soon as sirens started getting close by, the melee evaporated.

Michael Lee:

The other side of the coin was the secret show, like the Strokes or the Beastie Boys. Patti Smith. Those stick out. There was one little shitty service bar in the back, and then we’d all work in the main back bar. One bartender got to work in the showroom, so you’d fight over it if you really fucking didn’t want to be in the room, or if you really did. My worst memory was five nights in a row of Train, like, hot off of “Drops of Jupiter” or whatever. It was a fan club-only Train five-night run. Amongst the bartenders, that was hilarious. I was new, so I think I had to work four out of the five shows (laughs).

Val Kiossovski:

Christine Wood diligently kept booking Death Cab for Cutie. She’s probably one of the people that catapulted their career.

Michael Lee:

The music scene in Seattle in the mid-2000s was vibrant, and the staff at the Crocodile was reflective of that. Josh Tillman was a door guy there, and a dishwasher. His humor and wordplay was totally intact — the Father John Misty we now know him as. He was just a sarcastic ruffed feather there. He used to play as J. Tillman, before he joined Fleet Foxes. He’d get gigs opening for larger mid-level artists, but often he’d play a Tuesday. That’s what I remember really liking too, as a musician. If you got invited to play a Tuesday, and you were good, and you brought some people, then you might get to play a Thursday next time. I don’t know many venues that operate that way of very deliberately nurturing the local scene. Inevitably, some of that talent is going to be lousy. But some of it will pop up like a diamond in the rough on a Tuesday, and then you open up for something larger on a weekend night, and that starts careers, at least locally.

WHAT WAS EVERYTHING? THE CROCODILE CLOSES (2007), THEN REOPENS (2009)

Robin Pecknold:

I remember it being like it was any other night, and then we were all really surprised that it closed. It was me and Damien Jurado and Josh Tillman. I never really did solo shows back then, but I think they just asked. Maybe they knew it was closing and they wanted all the current sad bastards moaning the place to death one last time.

Michael Lee:

Val and I had opened Solo Bar already, but I kind of kept my foot in both just because I wanted to see shows and see friends. I still worked once a week in the bar in the Crocodile. I went there one night in December of 2007 and hung out in the back bar until 4 in the morning. We were all having fun, unknowing. The next day, the doors were locked and it was over really, really fast. We had no idea. I almost felt like somebody was watching us from the outside and saw us leave at 4:15 and then got us in trouble. It was very abrupt. The staff didn’t know. It was Christmas too, so there was a fundraiser at Chop Suey for all the employees. That Robin and Josh show was cool, but it was unremarkable in the grand scheme of things. It didn’t seem out of the ordinary that such a bill like that would happen, and that if it did, it would happen at the Crocodile.

Nabil Ayers:

What was crazy was that all the shows just got shuffled around to other venues. I remember seeing a show at Neumos with MGMT, Black Mountain, Yeasayer and somebody else. It was basically two shows: the one that was supposed to be at the Croc and the one that Neumos already booked. For a while, there were these four or five band bills at other places simply because the Crocodile had closed.

Michael Lee:

To my knowledge, the staff literally wasn’t told anything ahead of time. There were whispers around that others were interested, or that it might be for sale. Two weeks before the closure, the booker Eli Anderson was adamant about the Crocodile not being for sale and they were just tweaking some things, but then sure as shit, two weeks later, it was closed and padlocked. I got hired in the cafe originally. The writing was a little more on the wall, now that I can see the big picture. The cafe used to function as a restaurant, and then there was the back bar and then the venue. They ditched brunch, and then they ditched lunch. And then it was like, is the cafe even open for dinner? The food thing fell by the wayside, but it was indicative of Seattle in the moment and the rise of Amazon. Belltown was changing, and that was concerning. The only heartbeat was the back bar and the revenue that came from booking music. Cute things like rummage sales on Sunday brunch went by the wayside, and it was this skeletal music situation. That was the unenviable position for someone like Eli. It was a large task to undertake, and he did a great job. It was probably insurmountable to ask one human being to be a savior and pick up all that slack.

Hannah Levin:

To be honest, I was shocked and dismayed. I was fucking angry. I actually remember going home to my boyfriend and saying, “I’m done. Fuck this. If the Crocodile’s not here, I want to move to Austin.” The staff showed up and the door was locked, with a chain on it. Usually when a place is closing, you get a little bit of notice, so you can go pay your respects and have one last patty melt. But it was so sudden that no one got to say goodbye.

Val Kiossovski:

The scene eventually changed in musical terms. What was hip and cool and developed over the years was not necessarily available anymore — those bands got too big. The talent coming from underneath was not necessarily the right talent for that type of venue. Stylistic preferences changed. The Croc didn’t necessarily keep up with that, which is normal. I see it with venues all over the world when I’m on the road. Everybody specializes in something and does it really well. But the Croc was still pretty diverse in terms of the type of bands booked.

Susan Silver:

Sometime in 2008, [Alice in Chains drummer] Sean [Kinney] calls me up and says, “Silver, we should re-open the Croc. This place shouldn’t be sitting there.” I said, “you know what, dude? We know a lot about what’s great when you go into a venue, what works sound-wise, stage logistics, and what makes a dressing room an inviting place versus punishment, but we don’t know shit about running a club. So, nice idea, but I pass.” Then, six months or a year later, I got contacted about an investment group being put together to renovate and reopen the space, spearheaded by Marcus Charles, who had opened a lot of restaurants and bars. At that point, we said, “absolutely. We’re in.” For me, the bathrooms and dressing rooms were paramount. It was fun to put my Tetris skills to work and maximize storage and comfort. There was no way to make this club new while trying to recreate those infamous bathrooms. They were a little bit scary. They just were. Why try to emulate that? It wouldn’t have been authentic anyway. We took it in the opposite direction. We have a friend in Seattle, an amazing artist named Jesse Higman, who is a paraplegic. He does some of the most detailed artwork I’ve ever seen. I was visiting him in his apartment in Capitol Hill and went in to use his bathroom. He had the wheel-in shower done in white subway tile. I said, “This is it. This is so beautiful and timeless and indestructible.” Hence the white subway tile.

We were growing up. We thought, let’s make it pretty while still functional. The marble counters were probably a bad idea, but it was sure beautiful. The dressing rooms became the place where the graffiti ensued, which was nice. It was like a tour book from all the bands, adding their missives to every nook and cranny. Sean took over the production. He made sure the stage was big enough to be comfortable, and that the sound and lights were amazing. Those are the sorts of things that traveling musicians take on to the next place and tell their friends about. That sort of professionalism creates good will in the touring band circuit. If they’re not treated respectfully, the club gets that reputation. We wanted people to leave feeling well taken care of.

Val Kiossovski:

I thought the way the bar was set up didn’t have the communal vibe of the previous space, even though the previous one was complete and total chaos. You could still smoke back then, and I swear to god, I could have sliced the air with a knife, the smoke was so thick. At the new Croc, that didn’t happen. The old Croc had this necessary grit in it. It was a matter almost of life and death to make the show happen and make it right. However, the new showroom turned out to be very friendly and the new stage was amazing. It was now designed like a proper rock club. I’ve always had good experiences at the new Croc, in terms of the crew and how professional they were.

Susan Silver:

Seattle kept being a home for creative people to flourish, so the Crocodile was again a consistent part of that. When Stephanie had it, it was a great place for both musicians and the audience. We tried to emulate her model in creating a great experience for the musician and the client. Great music kept happening, and we had some great bookers. We used that back room, instead of it just being a bar, to accommodate small shows. With the building of the mezzanine, we could accommodate all ages at the same time. That was satisfying. Having cut my teeth at Metropolis, it was so important to me that there were all-ages opportunities.

Ken Stringfellow:

The Crocodile was our venue of choice in 2010 when the Posies debuted all the songs for the album we were about to go record in Spain. That was an important night for us.

Robin Pecknold:

I remember people saying, “Oh, it’s not the same anymore. It’s so much nicer.” Early on, in a Seattle-y way, people were afraid of change. But I loved the new one. Whenever I was in town, I’d always end up there. We had our “Crack-Up” tour finale party there. They were super nice to let us rent it out as a private thing after Bumbershoot in 2018.

Michael Lee:

When you spend so much time in a place for so long and then it goes through a transformation, there’s immediately going to be heartstrings that are pulled just because it’s not what you remember. That doesn’t make it better or worse, but I remember being shocked at first, because it wasn’t a small renovation. They ripped out the cafe, and the back bar became a pizza hang. The chandeliers in the back bar are still there, and the booths, and the colored stained-glass windows. As a net takeaway, they made it fucking incredible. It became a state-of-the-art venue. The charm of the old Crocodile was that it was sort of held together by some duct tape, and this was not the deal anymore. It smelled clean and it looked clean, and that was shocking. But it was such an improvement.

GOOD THINGS COME IN THREES

After having closed in March 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Crocodile is embarking on yet another chapter. In its new location not far from the original spot, the venue will sport a 750-capacity showroom, 300-capacity small club, 96-seat comedy club/theater, an art gallery, a streetside bar and grill and an 18-room hotel.

Susan Silver:

Marcus informed us that the owners of the old building, who we hoped would sell it to us, had in turn priced it out of the market. It so happened that this big, beautiful space down the street a few blocks became available, so that is where the Crocodile will be moving. The restaurant El Gaucho used to be there, as did the Sailors Union of the Pacific, which hosted shows in the ’90s. As the months went by, we inherited the whole building — not just the two showrooms. They’re in super demo phase right now, so there’s not a lot to do before construction starts. It’s exciting. The hotel was in functional shape already, so a woman named Jena Thornton is updating a few things. It’s one thing to have a hotel above a restaurant, but to have it above a rock venue…I’ve never experienced that (laughs). Hopefully people will find having rooms right above the stage exciting.

Nabil Ayers:

El Gaucho is where you would see high-end prostitutes and famous Seattle athletes (laughs). Record label reps would take us there before shows at the Crocodile. In a weird way, it feels apropos to move there. If they can get the right shows and the room is cool, people will go. It would be amazing if it worked, and I hope it does.

Val Kiossovski:

Normally, it doesn’t work when a venue moves locations. If I was in their shoes, I wouldn’t try to recreate the old experience. The name will carry on. It has clout and such a legacy. I hope that it works, because the city needs something like that. From what I’ve heard, they’re diversifying into different spaces, and I think that’s a fantastic idea. It gives them a leg up on the competition, because it’s a very desirable space for artists.

Nils Bernstein:

I’m so excited for it to still exist in any form. I’m excited for it to grow and be in a space where they can be more ambitious. CBGB is a good comparison. It had some amazing stuff going on in the ’90s, but it was unrelated to what went on there in the ’70s. A lot of the Croc had to do with what the Seattle scene was like in the ’90s. You can’t think of the Croc in whatever incarnation it takes now in the same context as the ’90s, because nothing is the same. It might be better in a million ways, but it will be different. In Seattle, all the development is bad. Everything is expensive. Anything old is gone. But people are psyched. It seems amazing that it is even still intact, let alone starting a new chapter.

Scott McCaughey:

The Crocodile had a lot of faults. The roof would leak. There were a lot of problems, but it was magical somehow. I actually played there before it was the Crocodile, when it was a Greek restaurant called the Athens. I played punk shows there in like 1980 or 1981. When I first went to the Crocodile, I was like, “Oh, I remember this place!” It was already living a second life then, you know? It became something different when it reopened in 2008, but it was a really cool place in different ways. This new place will probably be really nice too. The people who run it are people who have been in the music business in Seattle for a long time, and they care. They’re good people. I’m really happy that they’re going to try to keep it going.

Robin Pecknold:

Look at Zebulon. It moved from Williamsburg to L.A., and it is thriving. It seems like the L.A. iteration is even more important to their concert landscape than even the Williamsburg one was. I think there’s precedent for that kind of thing working, as long as the spirit remains the same.

Ken Stringfellow:

Seattle is getting crushed between economic pressure on the arts and COVID, so you can’t imagine a worse situation for venues right now. The Crocodile, for Seattle-ites, is iconic, so people would like to see that legacy represented somehow, especially now. The funny thing is, the Posies played at the Sailors Union of the Pacific [Hall], so I know the room. I ate dinner there a few times too.

Michael Lee:

I’m cautiously optimistic and excited. If the second iteration is any evidence, then it will be incredible. I like that they will have three different showrooms of different sizes. It speaks to the mission of the original Crocodile. They’re spreading the tentacles to involve as much of the community as possible, whether it’s comedy or art or theater or whatever. With the changing demographics of Seattle, I think that’s shrewd, and, if done correctly, destined for success.

Jerry Everard:

My focus in the past has been on how much you put into a place, in terms of how you fix it up, how people move around and how you build community. But once that community is built, it could be transported if done right. The dynamics are so different now. Belltown has changed so much. There’s no longer the practice spaces and people aren’t living there anymore. So now, really, what you’re talking about with the Crocodile isn’t can you move that thing that made it originally to the new place, because that doesn’t exist anymore. You’re talking about the legacy of that and the ability to draw people to come play there. I think you can do that. They have to figure out how to make it so people feel ownership of the space. That’s what the Crocodile did originally, and that’s going to be the real challenge moving forward.

“I keep telling my daughter, like Eddie Vedder so poetically said, ‘It’s evolution, baby.'”

Susan Silver on the Croc’s latest iteration

Susan Silver:

With age, the one thing I’ve learned is, shit doesn’t stay the same. I am a sentimentalist, tried and true. The idea of institutions changing in any form makes my heart hurt a little bit. Seattle itself has gone through such an explosion. It breaks my heart to think of places like Bad Animals studio being gone, but it’s the nature of life. I keep telling my daughter, like Eddie Vedder so poetically said, “It’s evolution, baby.” We had the most cranes on the skyline of any major city in America at one point, with all the condos and the apartments and Amazon. It’s not something we could stop, so how do we make the most of it? I’m glad the partners decided to take another chance. For this to happen during the pandemic was one of the signs of healing, in that we invested in a future where people would be able to gather again. We hung our hats on things working out and that we’ll be able to gather again soon. If the Crocodile can be a sign of hope for us, all the better.