This story is part of the Fall Travel issue, which is on sale here.

These days, it’s tricky making an excursion to the desert from Southern California. The desert, of course, is shorthand for the area encompassing Palm Springs, Joshua Tree and Yucca Valley. What was once a refuge to an intriguing mix of (depending on the location) hippies, artists, outlaws and retirees has become to Los Angeles what Montauk is to New York City. Which is to say: It’s overrun with an un-self-aware social-media crowd who’s driving up prices, creating gridlock and challenging noise ordinances.

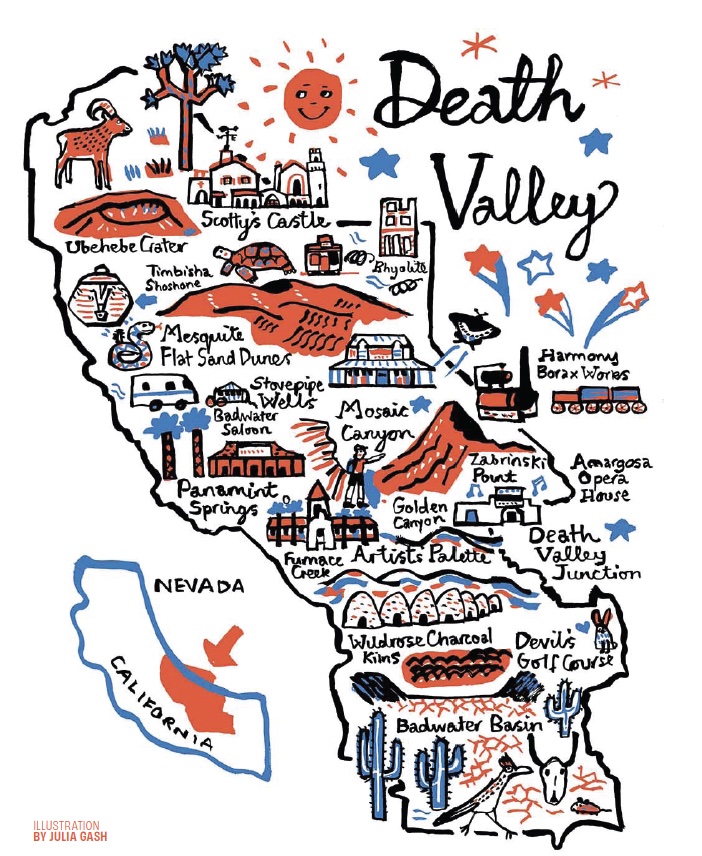

That’s why I became a Death Valley devotee. Its name notwithstanding, Death Valley is a wild mix of eccentric locals and good-natured naturalists, who live among hyperreal panoramas (some earthy, others colorful) and old-timey settlements. For many, a visit here borders on spiritual.

Death Valley is massive and, at 3.4 million acres, the country’s second-largest national park. It sits at a very low altitude while being surrounded by towering mountain ranges — two things very efficient at trapping heat. In 1913, temperatures reached 134 degrees Fahrenheit (the hottest ever recorded), and just four years ago, they hit 130 degrees. It’s called the Hottest Place on Earth for a good reason.

This desert is roughly 100 miles from Las Vegas and 275 miles from Los Angeles. Though it seems like a convenient sunny weekend trip, never visit Death Valley during the summer. Mother Earth will deal you her hottest hand, and you’ll fold. Wait for the winter, and the weather can be snowy and unpleasantly cold. And while the promise of wildflowers may lure you there during spring, every other traveler had precisely the same idea. The optimal time to visit is mid- to late October, which kicks off a camping season of balmy days and cooler nights. It’s also your best chance for the solitude of serenity.

If you do find that serenity here, it can feel like striking gold. “We need wilderness whether or not we ever set foot in it. We need a refuge even though we may never need to set foot in it,” wrote the famed environmental essayist Edward Abbey, in his 1968 love letter to the frontier, “Desert Solitaire.” He penned his book in a former brothel, adjacent to the geothermal Devils Hole just outside of Death Valley. Abbey’s angst over the trappings of modernity, and the need to detach from it, are undying sentiments. Sometimes it’s healing to be small and tacit, as nature muscle-flexes in a preternatural setting. “We need the possibility of escape as surely as we need hope.” That is why you visit Death Valley. Here’s how I’d spend a long weekend there.

Enter the park through Death Valley Junction

To ease yourself into this terrain, enter through Death Valley Junction, a town just east of the park, and pop in for a peek at the dusty opulence of the Amargosa Opera House. Built circa 1923 in Spanish Colonial Revival style, this cinema sat abandoned for decades before dancer Marta Becket turned it into an opera house in 1968. The Opera House, which makes a cameo in David Lynch’s “Lost Highway,” was built toward the end of the area’s mining boom for borax (1883-1889), the mineral used in everything from cleaning solutions to metallurgy.

Most of what you’ll want to see unfurls northward from Amargosa, inside the national park. As you make your way through the park, you may encounter abandoned towns and rogue mine shafts. If you’re one to drive off paved roads, be aware that the park’s unofficial roads can be very rough and require a formidable vehicle with four-wheel drive. Also, with very little cell service, your mobile phone is virtually useless. Although this heightens the isolation of Death Valley, you need to plan accordingly.

Artists Drive

Your eyes will thank you for taking Artists Drive — nine miles on a dipping, winding road — to Artists Palette, mind-blowing hills that are pastel-hued thanks to metallic volcanic deposits. This is your Kodak Photo Spot. When you’re ready to take a relatively easy hike, Artists Drive leads you to Golden Canyon, where you’ll find yourself ensconced between massive yellow canyon walls. Lastly, swing by Devils Golf Course, a field of large salt formations with a lunar vibe.

Watch sunset at Zabriskie Point or Wildrose Charcoal Kilns

Due north is the main attraction, the stunning Zabriskie Point, which overlooks the badlands and has streaked hills, brush-marked by erosion. Zabriskie is where French philosopher Michel Foucault’s mind was blown (to be fair, he was on acid), the site of director Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1970 counterculture film and, rather ironically, the spot where Anton Corbijn photographed U2 for the cover of “The Joshua Tree” album.

Zabriskie Point is one of my two favorite sunset spots. The other is Wildrose Charcoal Kilns, 10 giant beehive-esque structures built in 1877, wherein the Modock Consolidated Mining Co. once made charcoal to fuel local mines. These surreal kilns make for haunting backdrops during the golden hour.

After sundown

If you’re an outdoors person, Furnace Creek Campground is one of the park’s most popular spots to tuck in for the night. If you’re not, I’d recommend the newly renovated Oasis at Death Valley at Furnace Creek, which has a pair of options: The Inn at Death Valley, the nicest resort in town, and its sibling, The Ranch at Death Valley, a more affordable option aimed at families. It’s also a solid spot to get a meal, whether at the more upscale The Inn Dining Room — think steak and seafood — or at the Wild Rose Tavern, which serves pub-type food. If you like fine dining when you travel, take note: The cuisine in and around Death Valley is simple Americana fare, which is part of the charm.

If you’re on a tighter budget, I’d advise skipping the other hotels in the park: The Stovepipe Wells Village and Panamint Springs Resort are both underwhelming yet overpriced. (However, do consider a meal at Stovepipe’s Toll Road Restaurant and Badwater Saloon, both of which serve unpretentious food with a Southwestern flair.) Instead, consider the previously mentioned Amargosa Opera House, which is attached to a stuck-in-time, allegedly haunted hotel that’s still operational and best classified as artfully shabby. Or peruse Vrbo or Airbnb for lodgings — many chic, some unconventional — in areas just outside the park. Finding hole-in-the-wall bars peppered with colorful locals is the best perk of staying beyond the park’s boundaries.

Stargaze under some of the country’s darkest skies

If the sky is clear, venture out after sundown for a breathtaking DIY constellation show. According to the International Dark-Sky Association, Death Valley is so devoid of light pollution that you can actually see astronomical objects you can’t see elsewhere. To that end, the National Parks Service has designated four locations to enhance your stargazing pleasure: Mesquite Flat Sand Dunes, Harmony Borax Works, Badwater Basin and Ubehebe Crater.

See these sights in the daylight

Each of the stargazing sights is a 24-hour attraction: as satisfying in the day as they are at night. Take the next day to visit them. The desolate Harmony Borax Works ore plant sits just north of Furnace Creek, home to the Timbisha Shoshone peoples, the area’s original settlers. (It’s taken generations for the Timbisha to reclaim their land, which they finally achieved in 2000 after the federal government ceded roughly 7,700 acres to them, of which 300 acres are located at Furnace Creek.) Nearby, you’ll find the Mesquite Sand Flat Dunes, one of the most recognizable Death Valley locations (from 1977’s “Star Wars”). A frontier of voluminous sand and the occasional cracked clay ground (a former lakebed), the locale is peppered with cool, twisty mesquite trees. Meanwhile, Badwater Basin, a trippy salt flat that sits 282 feet below sea level, offers a stellar view of the 11,000-foot-tall Telescope Peak. Since you’re already down there, head to Dantes View, which stands above the Basin and is often considered the best vista in Death Valley.

Ubehebe Crater is about 45 miles away, but worth the jaunt. A half-mile in diameter and 600 feet deep, it’s an imposing reminder of what happens when steam and gas cause an explosion. While you’re up there, swing by Scotty’s Castle, a Spanish Colonial-style villa owned by a prospector, and Rhyolite Ghost Town, which is at the edge of Death Valley. A memory of doomed gold-rush bravado, it’s a fitting denouement to your trip here: a makeshift townlet in the middle of nowhere, where the remains of everything from a bank to a brothel lay, rather hauntingly, in state.