This story is part of the Fall Travel issue, which is on sale here.

A ghost story for you: a decade after Founding Father Thomas Paine’s death, a man named William Cobbett dug up and stole his body. Cobbett managed to carry his bones across the Atlantic Ocean to England and attempted to sell pieces of Paine’s hair like relics. Shockingly, no one bought any. After Cobbett’s death, Paine’s remains passed from person to person until eventually they disappeared. I hear this story for the first time as I stand across the street from Marie’s Crisis, a show tunes sing-along piano bar in New York City’s West Village where the world’s most enthusiastic pianist once scolded me for not knowing the words to “Don’t Rain on My Parade.”

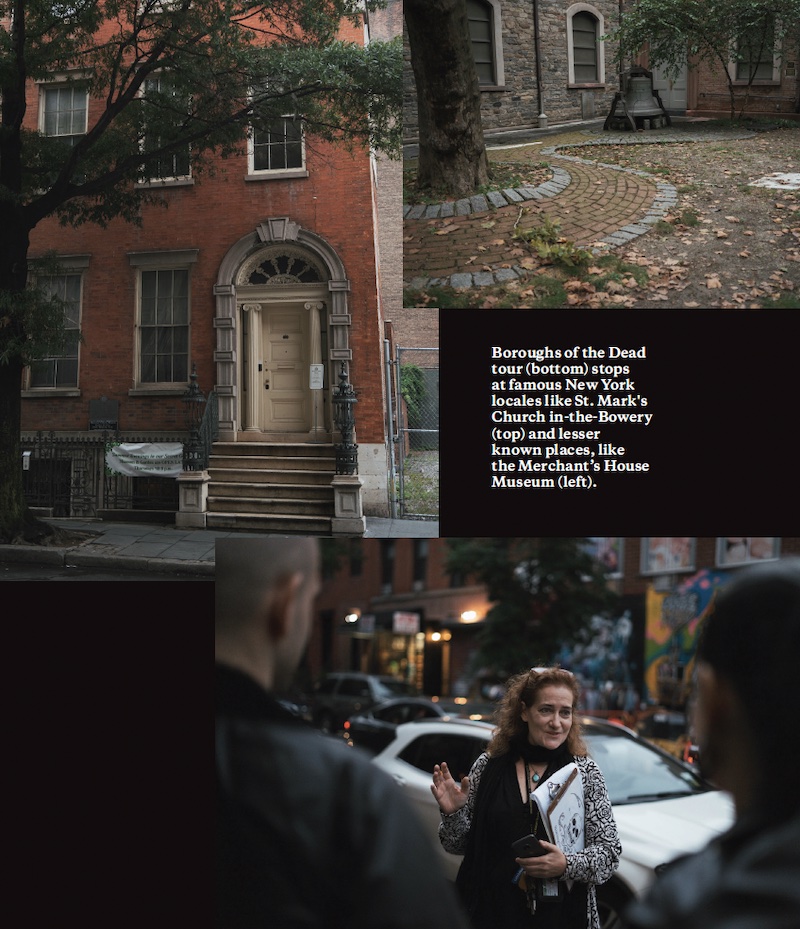

My visit this time doesn’t involve a Streisand impression. I’m following a guide from New York City’s historic ghost tour company, Boroughs of the Dead. As the group looks across the street, our guide, Melanie Feaster, whose dangling skeleton earrings shine a little bit in the sunlight, tells us that Marie’s Crisis occupies the bottom floor of a building that was once Thomas Paine’s home and the site of his death. Reportedly, despite what happened to his body, his spirit stuck around as the building eventually became a brothel, then a bar.

If you haven’t heard, ghost tours are in. Haunted attractions generate an estimated $300 million dollars annually, and unsurprisingly, fall is their boom time. Haunted tours have a reputation for being a little wacky, and ghost-oriented shows like “Long Island Medium” or “Ghost Hunters” have done little to change this perception. However, some ghost tours across the country can provide more than an eerie walk through an old building. While some might focus on proving the presence of spirits, a significant number of these tours combine the heebie-jeebies of good old-fashioned ghost stories with accurate histories of local places and people. They’re a way to talk about true stories of wrongful deaths or people confined to asylums, and to visit places we might otherwise turn away from, like abandoned buildings, battlefields and penitentiaries. Go on a tour this fall, and you may get spooked, but you’ll also learn something.

We aren’t the first generation to look to ghost stories to teach us something about the world, about ourselves. (I mean, you’ve heard of “Hamlet,” right?) In the United States, the roots of current fervor for ghost hunting and tours can be traced back to the 19th century. More specifically, the moment when two young girls living near Rochester, Kate and Maggie Fox, heard a spirit knocking on their walls. They said they knew just what he was trying to say. The press picked up the story, the sisters continued acting as mediums, and the Spiritualism movement took hold.

Large numbers of people began believing that the dead are among us and trying to tell us something. Mary Todd Lincoln hosted séances in the White House. Thomas Edison sought to create a kind of spirit communication device. The Ouija board began manufacture in Maryland in 1890. The ghost tours of today share some DNA with the séances of the 19th century. We’re still learning from ghosts, but on many tours, believing in them is less important.

On the Boroughs of the Dead tour in the West Village, our guide Melanie begins with the history of the area. We are on Lenape land (the Indigenous people of Manhattan). It used to be marshes and hills. Then the settlers came. The city got built up. Then she tells us that there are more than 20,000 bodies buried under Washington Square Park.

“Does anyone know what a potter’s field is?” she asks us as we stand on the sidewalk across from a Joe’s Coffee flying a pride flag. The six of us on the tour all shake our heads.

“It’s a common grave,” she says. A grave for unclaimed bodies, the bodies of enslaved people, people who died in epidemics, the poor, the homeless. The potter’s field that later became Washington Square Park operated for a little over 30 years around the end of the 18th century. Knowing about the bodies feels spooky, yes, but also a little like grief. The emotion is born from an irrefutable fact. The story didn’t require me to buy in. It’s just true.

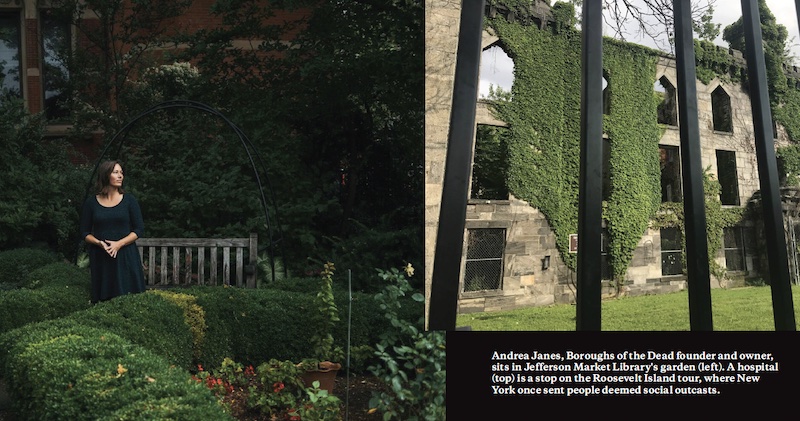

Andrea Janes, the founder and owner of Boroughs of the Dead, falls more on the skeptical side of the spectrum when it comes to ghosts, but that doesn’t take away from her love of the stories. She started out as a food tour guide in New York around 15 years ago, but when she brought groups by Washington Square, instead of talking about pizza, she found herself talking about those bodies underneath the park. Pretty soon, Janes stopped giving food tours and started leading ghost tours.

“[Ghosts] work so beautifully as a metaphor, as a narrative device,” she says. “I find them fascinating, whether they’re real or not. I don’t really care if they’re real or not.”

Instead, ghosts are a way in. They’re fun, spooky and sometimes silly. They’re also an opportunity to tell difficult stories. Janes mentions Rose Butler, a 19-year-old enslaved girl who was hanged for arson in 1818. Hers was the only officially recorded hanging in the field that would become Washington Square Park. Boroughs of the Dead guides (and other companies) will often tell her story on their tours.

“Her story and the way it’s told on ghost tours really exemplifies the kind of fine line that we try to walk. We don’t want to be pedantic, and we don’t want to be joyless scolds or anything. But the fact is, we have this spooky hanging tree and the body and the soul of this dead Black woman being utilized for customers’ entertainment,” she says. So Janes strives for nuance, to tell the truth of the stories and the complicated histories they bring up, whether it’s racism or violence or gentrification, and let participants sit with it.

According to Heidi Aronson Kolk, a cultural historian at Washington University in St. Louis, the way ghost tours engage your emotions is part of what can make them a great counter to more traditional history tours. Ghost tours are supposed to unsettle you; that’s the beauty of them. Kolk should know; she’s gone on a lot of ghost tours. She started taking her university students on them as a fun alternative to museums, but eventually, she also started looking at them as something worth studying. In 2020, she published an article about how ghost tours offer a unique way to interact with negative history.

Kolk gives an example of just how much going on a ghost tour might get you in your feelings. Once, she took her students on a ghost tour in Memphis, Tenn., that stopped at the famous Earnestine and Hazel’s bar, which in its midcentury heyday was a jazz club with a hair salon and brothel on the second floor. Walking around upstairs, the tour guide told the group about a series of sex workers that were murdered there. The details were gruesome — Kolk remembers hearing that one woman was chained to a radiator. As the guide spoke, several people on the tour started feeling ill and had to leave. It wasn’t because the guide was necessarily prodding them for an emotional reaction, they were just telling the story. For Kolk, it was the kind of haunting that doesn’t necessarily need to have a spirit directly involved.

“It was like a contemplation of how violence leaves an imprint on a place,” she says.

Generally speaking, there are lots of stories of triumph on history tours. Here is the room where the Founding Fathers debated the Constitution. Here is where we dumped tea into the Boston Harbor. Here is where Herman Melville penned a Great American Novel. But when there’s not an easy narrative of triumph, when lives or communities are rocked for one reason or another, that’s where ghost tours can come in.

On another tour Kolk attended in New Orleans, despite the theme of the tour being centered around “gangsters and prostitutes,” she says in the middle of the tour, they started discussing Hurricane Katrina and racial divisions in the city. On another tour she went on in her hometown of St. Louis, they explored an abandoned brewery that had started in the same wave of German immigration that brought about Anheuser-Busch. It had changed the character of the neighborhood, but eventually failed.

“Haunted history tours often take seriously the character of local memory, the folklore,” Kolk says. “It’s less about whether it happened exactly the way that they’re telling you, and more about the need by the community to hold on to that story and tell it a certain way, and to know itself through the lens of that particular event.”

Which is one reason Kolk shares this piece of advice: go on a tour in your own city. It might make you feel more connected to it. She also has a second piece of advice: ask questions. The guides on these kinds of ghost tours are founts of information. They’re often retired teachers or licensed historical guides or local aficionados. They know more than just hearsay about a tall figure in a black cloak who swaggers down the street at night (although, obviously, get the hearsay too — this is a ghost tour).

One of the earlier stops on our tour of the West Village is a triangular building down the street from the Stonewall Inn called The Northern Dispensary. It stands on its own little island caught between Christopher Street and Waverly Place. For most of its history, Melanie tells us, it was a public health clinic. Edgar Allan Poe, the godfather of the spooky story, once came here to treat a cold. I love picturing him entering the building, which is largely unchanged, but most of what Melanie shares isn’t about Poe. It’s about how the clinic refused to treat HIV/AIDS patients in the 1980s, despite the fact that it sits in the midst of one of New York’s most well-known LGBTQ+ communities. The clinic was forced to close in 1989. The new landlord then left the building empty for decades. Three years ago, it finally became home to a nonprofit that delivers home meals to AIDS patients. This is why I love ghost tours, because in wrestling with our ghosts, this history is inextricable from that time that Edgar Allan Poe had a cold.

Tour Recommendations from the Experts