We all know the nation’s population is aging, but perhaps more alarmingly, its emos are aging. In a summer like any other in recent memory, America’s youths flocked to fields, pavilions and parking lots across America to fulfill a yearly pilgrimage. While some went to festivals to see indie pop’s newest it girl, or let loose for 72 hours straight, at new wave emo festivals, nostalgia is the Scotch tape that holds everything together.

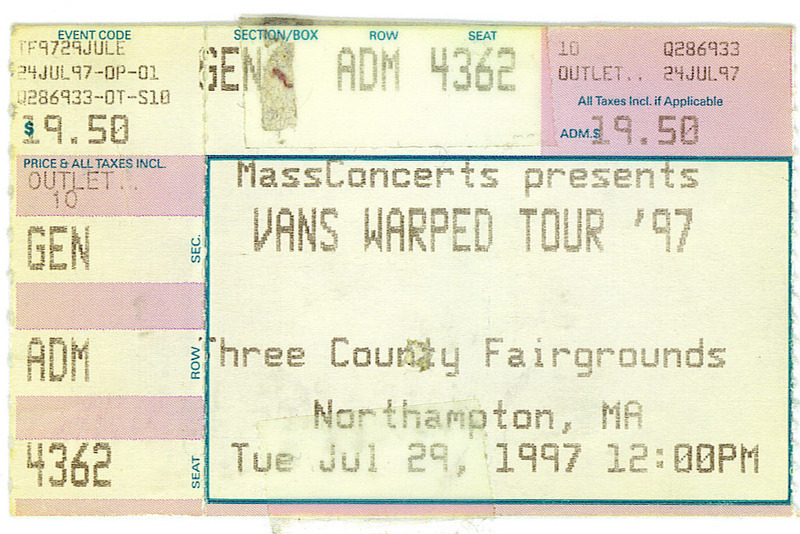

Since the sixties, music festivals have slowly grown from community-centered, counterculture hangouts into commercial behemoths. Day- and weekend-long music festivals rake in hundreds of millions annually, all backed by corporations punks historically railed against. Touring festivals up the ante in scale and cost, yet they’re an apparatus that has been taken up almost exclusively by alternative musicians, with metal, punk and emo variations. The traveling festival first made a name for itself when Lollapalooza hit the road in 1991, started by Jane’s Addiction’s Perry Farrell. No longer would teenagers have to make a pilgrimage upstate to Woodstock to get stoned out of their minds, or Chicago to sweat out a Four Loko in the summer heat. The circus would come to them. Lolla reigned supreme until 1995 when the Vans Warped Tour (dubbed “punk rock summer camp” at the time) overtook it as the largest and longest-running music festival in America. Since it departed from the scene in 2019, nothing has quite managed to fill its steel-toed boots, although many seem to be trying.

A genre that hinges on the extremes of teenage emotions, emo, short for “emotional hardcore,” or sometimes “fake punk bullshit for posers,” has flourished again on the festival scene with the same audience it had in the 2000s. Las Vegas has When We Were Young and Best Friends Forever, Canada has All Your Friends, but only one has taken on touring. Sad Summer Festival — which kicked off in Sacramento on July 12 and wrapped up on August 9 in Columbia, Md. — celebrated its fifth anniversary in 13 states this summer. The festival was born just as Warped Tour fell back into its Monster Energy-sponsored grave. In 2019, I hopped from one to the next over two weeks in the emo heartland (New Jersey), and the instant nostalgia factor was apparent. Only two weeks had passed since Warped’s demise, yet a new festival was already memorializing it. While the former famously attracted teenagers, Sad Summer and its peers are pulling in an eclectic range of former teenagers.

Can you teach an old punk new tricks? The answer seems to be yes, if you consider accounting to be a new trick. At Sad Summer’s New York City date on August 1, I could not pinpoint an audience member under the age of 21. If they were there, they were inconspicuous among a throng of 20-, 30-, and 40-year-olds drinking responsibly in the summer heat. I approached four girls who appeared to be the youngest present, only to quickly discover they were, in fact, in college — they just also happened to like pink cowboy hats. Much of the fashion, including that worn by the festival’s marketing team, towed the line between Williamsburg athleisure and Soho streetwear. Gone are the days of over-the-top goth-rock fashion and side-swept bangs. What used to be a sea of teenagers dressed in black has slowly become an amorphous blob of, mostly, aging millennials. Some have clung ironically to the wares of the late 2000s (an “I <3 Emo Bitches” T-shirt now stands out enough to be put on the big screen), while others have rejected them, opting for tote bags and pristine New Balance sneakers. It would be easy to mistake a portion of the audience for a fintech company’s Frisbee team.

The crowds are still energized, but gentler — polite, even — head bobs have replaced the violent thrashing of limbs punk shows are known for. One man looked so proud of himself when he emerged from the photo pit after successfully crowd-surfing that he waved his hand triumphantly in the shape of the horns as if to say, “I’ve still got it!” It’s understandable: Even at 24, one wrongly timed neck jerk can put me out of commission for the day. An older “former emo kid” sent me a message later in the day when I was complaining about an unfamiliar pain in my knees: “Take an Advil next time before you go! Adult tricks!” At 16, the only tablets I can recall seeing in line for a show were MDMA, which were shoved discreetly into mouths just before reaching security. Now, I’m sure it wouldn’t have taken me long to find a pain reliever.

The artists at Sad Summer — most of which made up the lineup at Warped Tour over a decade ago — lean into this. During We the Kings’ set, frontman Travis Clark paused at one point to say, “I know that was a lot for people with old knees,” after requesting the crowd squat down and quickly get back up again while they filmed a music video for a new song. And while they waved their arms and jumped as requested, this isn’t exactly Outside Lands, where new music is currency. The larger audience was only there for the group’s 2007 hit “Check Yes, Juliet.”

Clark, now 39, quite sweetly spoke about his four children before diving into another hit about forbidden teenage love. After them, Philly’s The Wonder Years took to the stage. The woman standing next to me, well into her 30s and very pregnant, immediately stopped discussing Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour with her friends when they began to play, squealing with equal excitement for them as for the world’s biggest pop star. The band followed up one of their most popular tracks, “Passing Through a Screen Door,” which contains the popular refrain “I don’t want my children growing up to be anything like me,” with newer addition “Wyatt’s Song,” named for singer Dan Campbell’s eldest son.

Between sets, chatter has changed as well, from excited talk of artist signings to career-based small talk. In-depth conversations about master’s degrees are happening beside a coffin at this festival. Sad Summer’s marketing has leaned heavily into its new, grown-up audience. The festival even sold its own craft beer at a few stops on the tour, a pilsner, in collaboration with Soul Purpose Brewing. It’s a beer that says, “I’m drinking this for the taste,” not, “I won’t remember today.”

It isn’t a new revelation that we’re in a nostalgia-bait period in larger culture. Y2K-based IPs are making a comeback, your favorite child star from the 2000s has a podcast, and adults with corporate jobs are showing up to festivals like Sad Summer in “Make America Emo Again” hats. Nostalgia is not a hidden pull at festivals like this, where bands are selling shirts that say things like “I Only Like Knuckle Puck and Lizzie McGuire,” but they fail to move past it, whereas mainstream music festivals like Gov Ball and Coachella are still attracting teenagers in waves — I was almost trampled by a hoard of them emerging from the LIRR in Queens back in June. So where did all the young people go?

In 2003, rock critic Jessica Hopper wrote in Punk Planet zine #56, “Emo is the province of the young…this is their inaugural introduction to the underground.” Emo is a lot of things, but it’s no longer the province of the young. If you live in a major city, chances are there’s a 21+ emo night happening at a bar near you this week. The community that existed in the 2000s, which itself grew out of the punk movements of the ’80s and ’90s, still exists, but it’s a funhouse mirror reflection of itself 15 years ago. For a genre of music that has multiple songs about the kids not being alright, they actually seem to be doing fine; they’re just old now.

Emo has also long since broken into pop music, with bands from the forefront of the Myspace era like Fall Out Boy and Panic! at the Disco leading the way into pop collaborations with Taylor Swift. Much of that music is not emotional or hardcore anymore. Emo historians, and I use that term as loosely as possible, put us in the fourth or fifth wave of emo, in which outlets like the Washington Post place artists like Olivia Rodrigo. Her rock and emo influences are clear (see a lawsuit involving emo darlings Paramore), but Olivia Rodrigo is not subverting the mainstream; she is the mainstream. What was meant to disrupt the zeitgeist in the 2000s is now passé; we haven’t even had a satanic panic this decade.

Punk has always been political, and undoubtedly left-wing at that. Just last month, Green Day had a lot to say about the former president onstage, to much right-wing dismay online. Warped Tour was a breeding ground for similar political statements. The Wonder Years used their time at Sad Summer accordingly. At one point in their set, Campbell took advantage of the microphone to say, “One, protect trans youth. Two, and I say this with my whole fucking chest, free Palestine.” Punk is at its core based on the ethos of fighting the powers that be. Most of those in attendance at Sad Summer may care about political activism, but they’ve definitely taken on a job at some point that could fall under the category of “the Man.” When I was 14, shows were one of the first places where I was exposed to large groups of people outwardly expressing left-wing ideology en masse, but kids today have new ways to talk about politics; TikTok just involves far less money spent on eyeliner.

In 2007, Hopper wrote in the Chicago Reader that “the idea that mega-festivals somehow create ad hoc communities out of their mega-crowds — an idea likely owed to Woodstock — is ridiculous. The only thing everybody at Lollapalooza has in common is the willingness to be painfully gouged for a ticket.” Warped Tour, for all its downsides, aimed to be a gathering place. When it ended, founder Kevin Lyman said, “I think we’ve lost the sense of community.” And yet, community, whether you want to call it a shared identity or maybe at this point a shared memory, is what initially drove Sad Summer’s founders to start the festival.

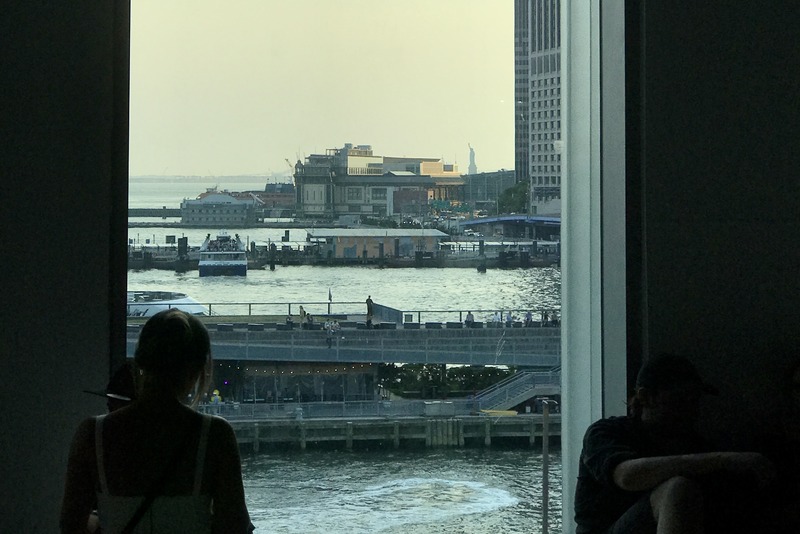

Sad Summer’s New York City venue, The Rooftop at Pier 17, was too small to fit all of the usual festival accoutrements of tents and activations within its solo stage. On my way out, I stumbled upon them, hidden in a large, unfinished concrete room on a lower level, with large, floor-to-ceiling windows revealing views of Brooklyn and Manhattan. Former goths, mallrats and punks, who have scrubbed their appearances into upstanding adults, sat against cool concrete pillars, subdued by the heat. Around them, arranged between pillars as if on display in a modern art museum, were artifacts of emo past: knee-high lace-up Converse for sale, merch tents, a 12-foot inflatable sad bear. Relics, and yet, we’re all still here.