This story about Chicago’s dive bars is from our debut issue, Fifty Grande #1.

It’s just after 5 p.m. on a Wednesday when I walk into the Levee, an aging, cash-only corner bar on Chicago’s northwest side. Ferns and cream-colored couches furnish the entryway of this sprawling, decidedly ’70s tavern with Styrofoam ceiling tiles, stained-glass pendant lights, and an adjacent party room complete with billiards, darts, and a makeshift Pop-A-Shot basketball game.

A few regulars post up at the snaking brass-edged bar, where upholstered barstools resembling elongated office chairs sport one or two deep-set stains. Almost every inch of the wood-paneled walls is covered in framed jerseys, photos of community and youth sports teams, beer and Chicago Cubs neons, and a replica of the famous scoreboard at the Cubs’ home stadium, Wrigley Field.

Owner Warren Johnson, a Vietnam War Marine veteran and former semi-pro football player who bought the bar in 1979, walks over to take my order. He shoos away assistant barback Milo, a self-starting Golden Retriever who keeps propping his front paws up on the bar. The ice-cold bottle of Old Style I order depletes the last $4 in my purse, including tip.

In the era of ever-more-nuanced concept bars, I am grateful for no-frills joints like this one and guys like Johnson, whom you’ll find behind the bar each night despite his speech being almost totally compromised since suffering a mild stroke in the spring.

“He’s been going to speech therapy twice a week at the V.A. hospital,” says wife Renee as she deposits baskets of hot buttered popcorn.

You could call the Levee a tavern, beer-and-shot bar, saloon, neighborhood joint, perhaps even a dive. More poetically though, it represents the urban dweller’s historic living room — an egalitarian vestige of Chicago’s working-class industrial and immigrant roots, where anyone can walk in and shake off the day’s ills with a chat and shot of whiskey or cold beer that won’t break the bank.

The genesis of the third place

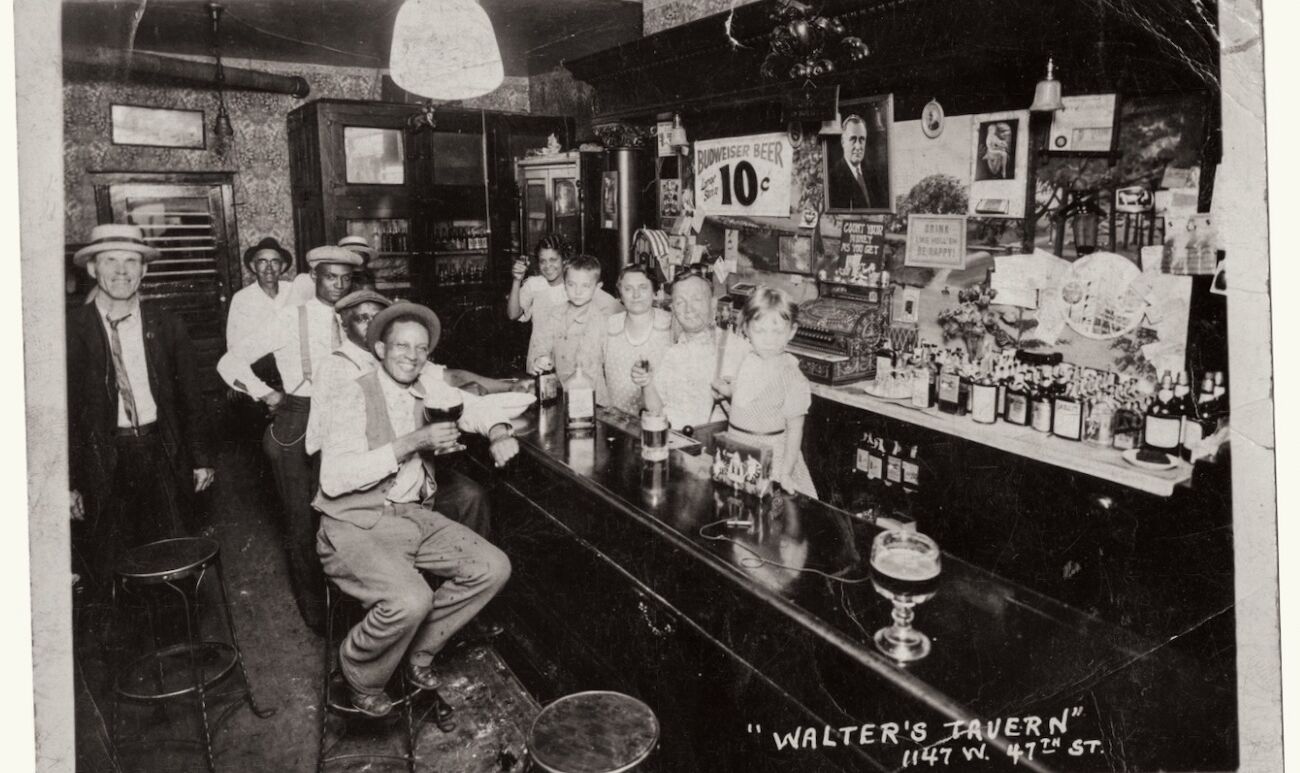

Almost every American city and town has its historic neighborhood taverns, which at times have served as community centers; meeting spots for union organizers, politicians and journalists; and gathering spaces for immigrants or marginalized communities. In the late 1980s, urban sociologist Ray Oldenburg dubbed this category the “third place” — informal spaces separate from home and work, where people go voluntarily to build community and tie one on.

In burgeoning, pre-Prohibition Chicago, like many cities, different bars opened up to serve different cultural and social purposes, as outlined by Perry Duis in “The Saloon: Public Drinking in Chicago and Boston, 1880-1920.” Opulent bars unfurled inside glittering downtown hotels, while 7 a.m. bars near industry plied workers with a nickel beer and free meal after long-ass shifts. Immigrant bars in ethnic enclaves allowed patrons to speak the language and dance to the music of their old countries; assimilated bars helped people adopt those of the new.

Following Prohibition, bar subgenres developed to suit different identities and interests, from gay bars to sports bars, art bars, cop bars, and cocktail lounges. But there remained those indispensable corner or midblock joints close to home, work, or an El stop, with cheap drinks and zero attitude.

Historian Bill Savage, a senior lecturer in English at Northwestern University, writer, and longtime bartender, likens them to another imprint of Chicago’s working-class roots, the hot dog stand: “It’s the same business model, with tight margins, providing inexpensive and vital things for the neighborhood.”

The problem with “dives”

The term “dive” originated in the 1800s, to denote an illegal drinking or opium den or other disreputable place, typically obscured so frequenters can “dive” in without being seen. Savage links it to the prevailing American Puritan Prohibitionist attitude that drinking, especially public drinking, was inherently sinful and shameful.

In the past 15-odd years, the term has become more descriptive and watered down, denoting a joint’s age or look — ripped barstools and general neglect. Some bars wear it like a cheeky badge of honor; the iconic Old Town Ale House self-describes as “Chicago’s premier dive.” A dive’s quintessential features (Brunswick bar, taxidermied animal busts) might even turn up in the business plan of a self-consciously chill concept bar where artisanal cocktails come in vintage tumblers.

Of course, there are still shithole bars populated by unsavory and self-destructive characters, where pool balls might become weapons if the wrong person walks through the door. But a place can also become a dive based on people’s attitudes about it.

“I’m not a big fan of the term, because it insinuates a location full of people who are, in a sense, less than,” says Liz Garibay, a historian who studies the role of alcohol in Chicago history.

This riles the likes of Garibay and Savage, as, they argue, it should anyone subscribing to egalitarian ideals. Like the hot dog stand or counter-service taqueria, the neighborhood bar represents one of a city’s truly democratic spaces.

“In theory, any member of the public can patronize any place that opens its doors,” Savage says. “In reality, people with less money or mobility will not be spending any time or money in higher-end places. But people who can drop $20 for an artisanal cocktail someplace downtown can drink at the corner bar where that same double-sawbuck will get you four beers with a generous tip. In a society riven by so many divisions, any place that offers the opportunity to connect across divides of class should be valued.”

What’s a dive, anyway?

I’m bellied up next to Savage and Pat Odon, director of beer and baseball operations at Nisei Lounge, one of a handful of dives left in fast-corporatizing Wrigleyville, much of which was bought up by the billionaire Ricketts family, who own the Cubs.

The bar’s name, meaning second-generation Japanese immigrant, hearkens back to its founding year of 1951, when Wrigleyville was an enclave for Japanese Americans who were relocated here after President Roosevelt closed the last of the Japanese internment camps late in World War II. By the ’70s, most of the Nisei who’d made that bar their third place moved to the suburbs. Now it’s a neighborhood joint for regulars like 24-year-patron Roger — who’s lived in the neighborhood since 1965 and whose preferred drink is Heineken — and a fan’s refuge for cheap pints and real darts before and after Cubs games during baseball season.

Today we’re here to parse the term “dive” and its approximates. Per Odon, a dive’s price point should be low, their patrons regulars. “This isn’t destination drinking. It has to be an everyday destination for somebody.”

That doesn’t mean a dive has to be welcoming, Savage interjects, pointing to a particular brand of watering holes on the city’s far southwest side. “Everyone looks at you, and if they didn’t go to grade school or high school with you, they look away. The bartender might deign to come down in five minutes. They’ll happily take your money, then you’ll go away and never come back.”

“Don’t send nobody nobody sent,” Odon replies, paraphrasing the famous late Chicagoan Abner Mikva, a former congressman, federal judge, and law professor, when he described his first exposure to Chicago’s machine politics. “That’s one reason I buy a shot of Malort when I’m in outlying neighborhoods. It gets them on your side.”

I’ve lost count of how many arguments I’ve had over what constitutes a dive, partly because they often come up after downing a few rounds at one of said contentious establishments. Does the Chipp Inn, a well-worn West Town corner bar open since 1897, qualify, since these days it fills with hipsters from the now-gentrified hood? Depends whom you ask. What about the old Bridgeport joint Bernice’s Tavern, where you have to get buzzed in? “That’s technically an art bar,” says Savage. Skylark in Pilsen surely counts. This beloved, cash-only watering hole in the shadow of a coal-fired generator’s skeleton was made famous by the 2006 movie The Breakup. Maybe, Odon says, but they serve food, which technically makes them a bar and grill.

This goes on.

Age might be the thorniest point of contention. Savage and Odon settle on a 10-year minimum. But Mark Domitrovich, CEO of Pioneer Tavern Group, which owns 85-year-old Chicago tavern Lottie’s Pub, along with the Pony Inn and Ina Mae Tavern, argues that a dive should endure at least 30 years.

“It’s something that’s definitely got some age, some patina,” Domitrovich says. “A real dive is a piece of history, a museum in the sense that time has passed it by, but it stays the same.” (By this calculation, the Pony has roughly two decades to go.)

Age is also symptomatic of a dive, in that most are inexpensive because they’re in less valuable and attractive real estate. “No new building will have a dive in it because the cost per square foot you’d have to get in new construction wouldn’t allow for the beer to be under $5,” Savage says.

All but refusing to succumb to this aesthetic prattle, Garibay contends that the community makes the joint. Her preferred watering hole is the Old Town Ale House, a seminal near-northside tavern with cheap beer and a great jukebox. She’s been known to leave her keys and wallet unattended there to run errands or deliver Chinese takeout to a regular’s apartment because he’d had one too many to eat it at the bar.

Bruce Elliott, a Chicago icon in his own right, owns the place; his politically tinged paintings fill every inch of wall space, including a nude Sarah Palin and bare-assed, disgraced former governor Rod Blagojevich. Now 78, the prolific Elliott shares colorful tales of his colorful life in a weekly podcast with Garibay, on his blog and in his book, “Last Night At the Old Town Ale House” (with an intro by the late Anthony Bourdain, who also loved the bar). Or stop by the bar to hear him in person while he sips Bud Light over ice, which he calls a “Polish martini.”

Like Maria Marszewski of Maria’s Packaged Goods (long since taken over by her sons Ed and Mike) or the late Jimmy Higgins of the bygone Higgins’ Tavern in West Lakeview, which opened at 7 a.m., Elliott and his bar are one and the same.

An endangered species

In the early 1900s, Chicago had more than 8,000 saloons; now the city’s bars number around 870. Following decades of battling the existential threats of deindustrialization, white flight, and suburban sprawl, now oldtimers like Elliott and the Levee’s Johnson face the enticing prospect of selling as gentrification claims Chicago’s downtown-proximate hoods, not to mention a dizzying, and growing, array of competitors.

The explosion of concept bars — from chichi craft cocktail lounges to arcade and darts bars, brewery taprooms, and now distiller bars and restaurants, street festivals, sporting events, concerts, the Riverwalk, rooftop, and hotel bars — all vie for drinkers’ attention. Home has never looked better either, with its massive TVs streaming every game and binge-worthy show in sharp-edged high definition, wet bars, and food and even bespoke cocktail mixes at our fingertips through Grubhub and Cocktail Courier.

But the biggest culprit could be technology, which has displaced the age-old bar argument over a missed foul call or shaky political debate performance to a handheld device. “You don’t have to go to the bar to say, ‘Oh my god, what’s Jay Cutler doing?’” Odon says. Simply log on to Twitter.

So what’s a neighborhood joint to do?

“Change or die,” deadpans Odon.

Some muster the energy to hang on and fight, building out their wine list or adding housemade, fresh-not-frozen tater tots. Nisei has developed a strong Twitter following with a voice to match its sardonic personality. A recent tweet read: “Bring in a pumpkin spice latte and for the low, low price of $5 we’ll pour Malort in it (and make you drink it here).”

Whether that translates to real butts in seats is harder to track.

But for those owners who’ve run out of gas, maybe, just maybe, the right buyer will come along. When Domitrovich purchased Bucktown dive Lottie’s Pub in 2002, it was rundown, its regulars a smattering of drug dealers making deals on bar property, ex-convicts, and people hellbent on drinking themselves to death. As he spruced up the old bar, Domitrovich took shit from all sides — regulars who didn’t want anything to change, neighbors who preferred to see the bar razed, even then-Mayor Richard Daley, who was on a crusade to rid the city of taverns and 4 a.m. bars, deemed “public nuisances.”

But Domitrovich saw Lottie’s for what it could be — a new third place for the gentrified hood with some connecting threads to the old.

“Third places are whatever you connect to,” Garibay says. “Taverns are anchors of that notion because human beings like to drink. That’s how these places survive; communities that drink are imperative to local, American, and world culture.”

Like the grandkids of the long-gone Nisei will wander into Nisei Lounge from time to time to see where their elders used to meet up, many of today’s Lottie’s patrons are the children of parents who fled to the ’burbs 20 years back to raise their kids. This generation is raising their kids down the street and bringing them to the bar to watch football on Saturdays. Ties to the old-school remain. One 28-year regular, Joe, who rebuilds drag racer engines in his garage, comes in every other night for Myers’s Rum and soda, convinced the drink keeps him alive. Another, named Gene, started coming in the day after his mother — a Lottie’s regular and bookie — passed away, and hasn’t stopped since.

Domitrovich has watched it all unfold firsthand from his near-daily post at the far end of the bar, where you’ll find him in his Lottie’s baseball cap.

“The architecture is one thing, but even just the history behind these places and what they mean,” he says. “You can’t tear everything down.”