Graffiti has what most art forms don’t: a unique, well-defined purpose. Graffiti seeks to bring glory to those who write it. The more noticeable the work, the more acclaim it receives. This objective takes graffiti writers and street artists to the tops of buildings to the depths of subway tunnels in their quest to paint avenues, apses, and elephants alike. Despite criminality and a nagging association with gang activity, graffiti and street art remain powerful cultural forces. They’re accessible. Barriers to entry simply include the cost of spray paint and the stones to do it. It would have been a surprise if it hadn’t started as teenage mischief, but what is surprising is what has evolved. Unencumbered by the legacy of a new artform’s looming giants and (mostly) the ambition of museums or galleries, graffiti took amateur artistic expression and dumped it into big city streets, democratizing it. Anyone could participate. Viewers could now witness that expression evolving in real time. From its earliest beginnings into what it is today—the most visible and mass market art form there is —here’s a very brief history of American street art.

Cornbread Rises in Philadelphia

Before murals were even a twinkle in developers’ eyes, street art began with graffiti. Even before that, graffiti began with simple tagging. The Philadelphia-based Paradigm Gallery states that tagging began with local artist Darryl McCray, aka Cornbread, in the late 1960s. In his late adolescent years, “he and a group of friends started ‘tagging’ Philadelphia, by writing their nicknames on walls across the city.” Today, the artist is frequently hailed as the “first modern graffiti artist.”

New York’s Subways Drip with Paint

Just as Cornbread and his friends began tagging Philadelphia for fun, the activity caught on and spread throughout the East Coast, especially in New York City. Teenagers scrawled their tags around their predominantly working class neighborhoods before focusing on subway cars in an effort to capture more eyeballs. Graffiti became a game for gaining attention. As such, eventually all of NYC’s trains were splattered with monikers, including those of early stars like Topcat-126 and Taki-183.

Martha Cooper Immortalizes the Movement

Although New York street art boomed straight into the 1980s, the average citizen regarded graffiti as a nuisance or ever-present eyesore. It was a criminal activity, not an art form — until Martha Cooper partnered with fellow photographer Henry Chalfant to print and release their 1984 book “Subway Art.” In an era without the Internet, this catalog of very timely images allowed graffiti writers around the world to see what was happening at the movement’s epicenter. “Subway Art” offered this ill-regarded art form the opportunity to exist through a cultured lens, one which exposed its innate beauty. It became the Bible by which writers studied their craft.

The First Big Stars: Basquiat and Keith Haring

Cooper and Chalfant existed behind the lens, though. Graffiti needed personalities who could lead the movement into the mainstream. Writers knew each other, and those who got their name out there most aggressively, and highest, gained a certain prestige amongst their peers. But fame only existed amongst those in the know, those who were hip to the game. Two New York-based artists, Basquiat and Keith Haring, made graffiti desirable to the masses during the early eighties. While Basquiat quickly transitioned into the fine art world with his irresistibly haunting entropy, Haring gained acclaim for his murals, whose bold colors and lovably anonymous characters lent the medium mass appeal. Both artists worked illegally on the streets though, which planted a seed in the collective consciousness. In doing so they directly connected the graffiti and fine-art worlds.

Cost and Revs Kickstart Poster Art in NYC

New York-based graffiti writers and artistic vandals Adam Cost and Revs tag teamed for a takeover of the city in the 1990s. Their secret? Newer mediums like stickers and wheatpasted posters. These artforms allowed illegal artists the opportunity to create detailed work ahead of time, mass produce it, and publicly distribute quickly. Stickers and wheatpastes also emphasized a rift that remains prevalent in this culture today — the boundaries separate a graffiti writer from a street artist, and how those two terms are defined. Cost and Revs influenced the adoption of stickered and wheatpasted expression at a time when New York’s lawmakers cracked down on illegal art and other petty crimes in a shift to “broken windows” policing.

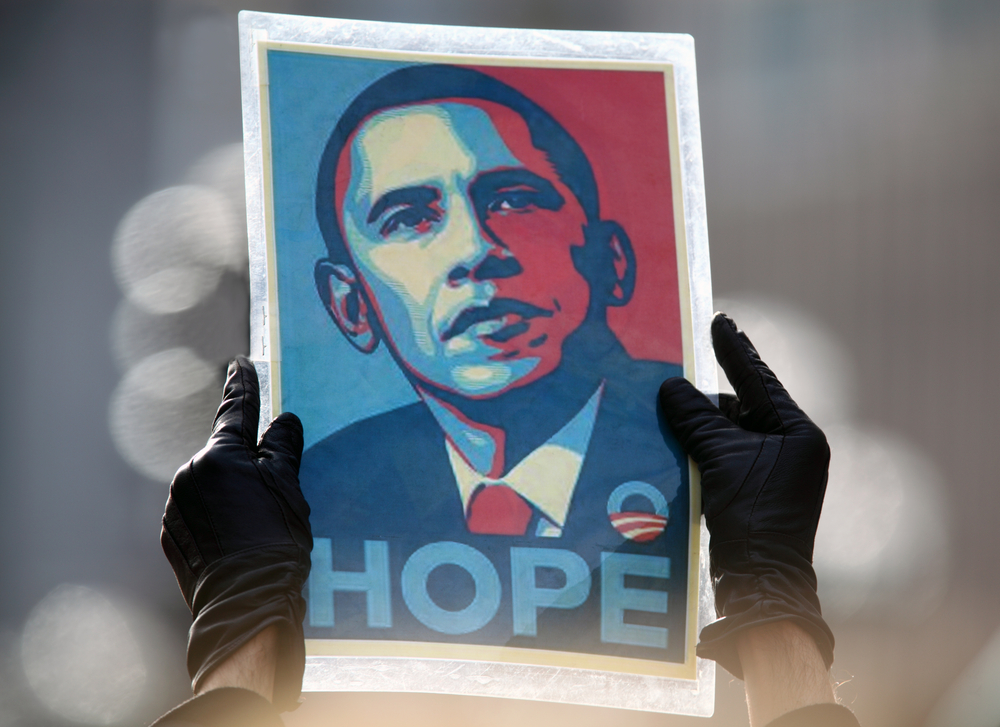

Shepard Fairey Takes the White House

Street artist Shepard Fairey possesses a unique knack for devising images with power and grab. He rose to prominence with his “Obey” (aka “Andre the Giant Has a Posse”) sticker campaign, started when he was an art student at Rhode Island School of Design, in the early nineties. By the end of the decade he co-founded a marketing company and had worked with established brands like Pepsi, Hasbro and Adidas. Fairey hit it big in 2008, when he was commissioned for then-presidential candidate Barack Obama’s Hope campaign. By this point, graffiti was an indicator of certain beliefs, even to the uninformed. Its incorporation in a visual landscape evoked attitudes of rebellion, of free expression, a gritty, yet cosmopolitan aesthetic. However, gaining endorsement from the Democratic nominee for President of the United States meant something even greater. It meant perhaps that the most powerful cultural institution in this country might be willing to align with the illegal art form’s ideals.

Wynwood Walls Stands Tall

With the proliferation of street art—which is more visually appealing than graffiti’s harsh lettering—illegal art no longer simply signalled that one was in a bad part of town. Instead, it often was a tip-off of a place’s hipness. Real estate company Goldman Properties used street art as part of neighborhood revitalization projects going back to New York’s SoHo during the Basquiat era. In 2009, they created a world-class outdoor street art gallery in Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood, a once crime-ridden area. The gallery, called Wynwood Walls, is now a legit tourist attraction which draws thousands of visitors to its energetic, rotating curation of international talent.

Banksy’s British Invasion

Street art’s rising cultural cache spawned a new generation of artists. To this day, no one has brought street art to the fantastical peak of fame that Banksy has been able to achieve. While the anonymous British artist has been active since the 1990s, he made his biggest waves in America when he debuted his ‘documentary’ titled Exit Through the Gift Shop at Salt Lake City’s Sundance Film Festival in 2010. This film came in tandem with a new series of Banksy works across the West Coast, and raised street art’s profile in the mainstream.

5 Pointz Meets its Demise

While street art gained increasing acceptance for its cheeky characters, stickers, wheatpastes, and gimmicks, its predecessor, graffiti, didn’t enjoy quite the same benefits. Developer Jerry Wolkoff acquired a factory building in Long Island City, Queens (NYC), during the early 1970s, and transformed it into artists’ studios in the early 1990s. Its new tenants overtook its facade, giving it an evolution of murals bursting with vibrant colors. The 5 Pointz building gained its name as the collision of artistic sensibilities from across the city’s five boroughs. Wolkoff whitewashed the walls after a decision to turn the property into residential housing, and then demolished the historic site in 2014. While the graffiti writers were awarded $6.7 million by a federal judge, this move proved a harbinger for the conflict street art would face in coming years.

Street Art, Capitalism Clash

As the business world embraced street art as a tactic in its marketing toolbox, artists bristled at the use of their intellectual property without compensation. In 2018, H&M entered into a legal battle with Revok when the company featured his art in a promotional video without credit or compensation. As Hyperallergic reported, “H&M denied his claims, arguing that the graffiti, which covers New York City property, is vandalism, and that Revok [had] no copyright rights to assert.”

Meanwhile, street art is flourishing in an increasing number of American cities, with many hosting their own mural festivals. Illegal public art and all forms that fall under its umbrella occupies a nebulous space right now. Only its artists know the real rules: getting out and getting up no matter what.

Related:

AMERICAN CITIES WORTH VISITING FOR STREET ART ALONE