This story was first published in The Hotels issue (#6) which hit stands in March 2024. 21c St. Louis was one of the properties named to our first-ever Greatest Hotels Ever list.

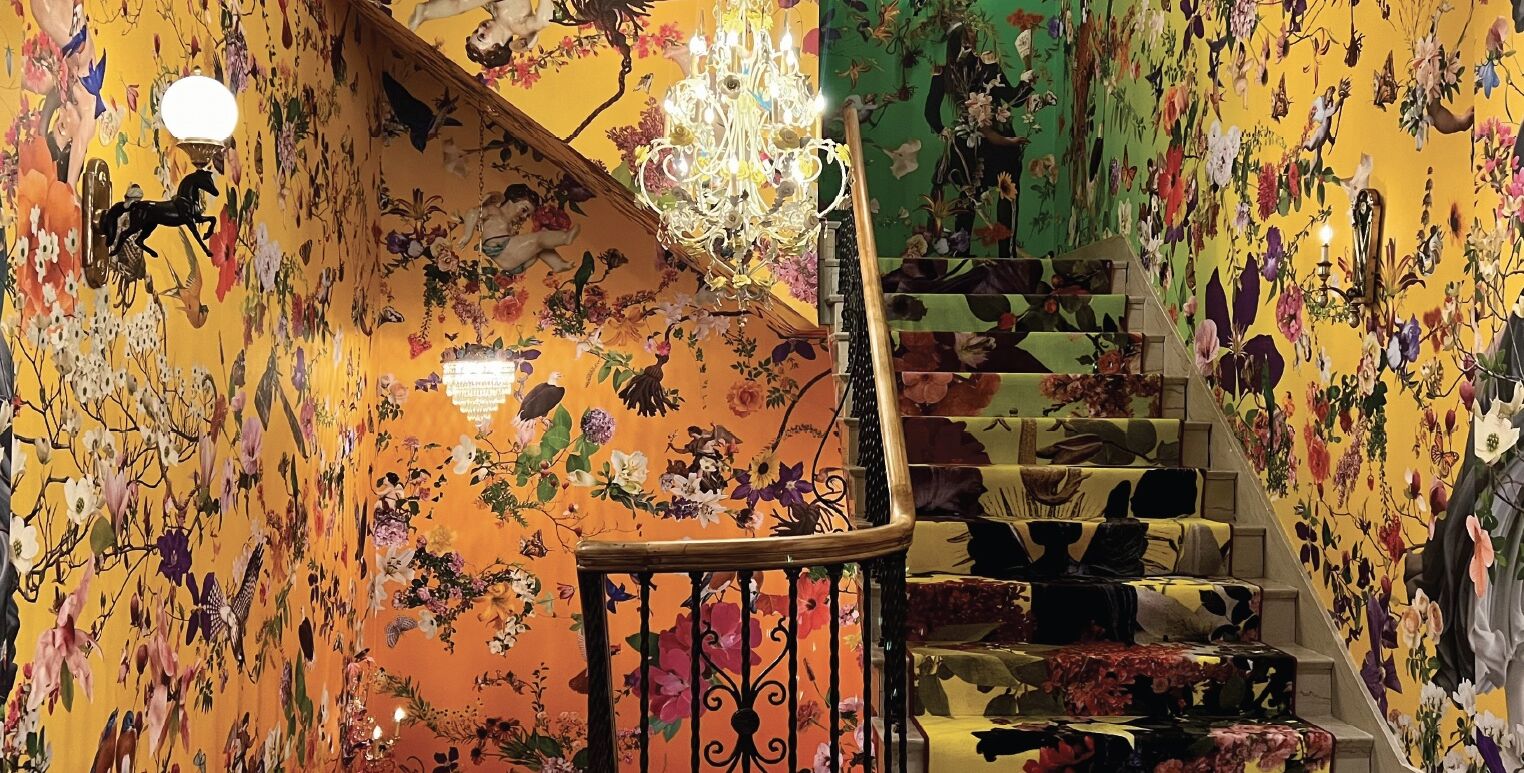

The newest 21c Museum Hotel only opened last August; however, “The Way Out West,” a three-story permanent installation occupying the lobby’s main stairwell (and on the cover of our latest issue), has already proven itself as St. Louis’ most iconic spot for a selfie. Sorry, Gateway Arch! Photo-printed wall coverings and carpets conceived by the design duo Fallen Fruit have become an irresistible backdrop where oversized cherubs tumbling across an acid landscape of flora and fauna camouflage slinging arrows and tomahawks among the dogwood. And if you turn around and take a deeper look, you’ll find even more subversive allusions to the city’s history.

“The Way Out West” is a nod to the 19th-century notion of Manifest Destiny, the idea of settling the American West as an act of divine will. That’s why you see Jesus on the floor next to the Faust beer barrel, a nod to the Faust Oyster House & Saloon, a favorite hangout of Budweiser creator Adolphus Busch. Museum manager Angie Villa walks me through it on a recent visit: “It’s like a Trojan horse; it’s so amazing and beautiful, dripping in decadence, but is full of complicated, painful stories built into it, just like the United States.”

“Take this safety pin,” Villa says, pointing to what looks like a keychain spanning several stairs. The photo depicts keys collected from Black-owned homes torn down to redevelop St. Louis Place, a nearby working class neighborhood. The cherubic imagery, meanwhile, comes from Campbell House, a neighboring Gilded Age mansion. “When money was pouring through the city back then, people looked toward European notions of wealth. Even the plants and flowers would have been brought here by settlers, the lilies and roses from Europe and Asia.”

The GIlded Age isn’t making a comeback in downtown St. Louis, but a couple of America’s most prominent and progressive art patrons are responsible for 21c opening here. Husband and wife Steve Wilson and Laura Lee Brown — as in Brown-Forman, the Kentucky bourbon behemoth behind Woodford Reserve and Old Forester — opened their first 21c Museum Hotel in downtown Louisville in 2006. Over the next decade and a half, they committed to opening properties that did more than revitalized neighborhoods — they challenged cultural norms. In 2012, they opened their next hotel in Cincinnati, where in 1990 a Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective was infamously accused of promoting obscene material; in 2013, 21c opened in Bentonville, Ark., a counterpoint to the nearby Crystal Bridges Museum opened two years earlier by Walmart heiress Alice Walton.

With each new hotel opening comes a new exhibition that travels between them; the St. Louis opening welcomes “Revival: Digging Into Yesterday, Planting Tomorrow,” occupying the hotel’s second floor, which includes a gloriously restored gymnasium, basketball court and running track.

The new 21c occupies a 95-year-old Renaissance Revival YMCA building. Nods to the predecessor rec center are everywhere, from the tiled basement lap pool, the jewel of the subterranean Locust Street Athletic and Swim Club, to the double-height loft rooms upstairs, the hardwood floors a holdover from when they operated as racquetball courts.

Before we head up the steps toward “Revival,” we make a pit stop at the bar of lobby restaurant Idol Wolf. Did I mention 21c was founded by a bourbon heiress? There’s another reason the hotel has proven such a popular selfie spot. Not only are the galleries free, not only are they open to the public 24/7, you’re even welcome to wander them with a drink in hand. Try that at the St. Louis Art Museum. (But really, don’t.)

“Revival” deploys works from top and rising Black artists from around the globe to explore how the past informs the present and future with different consequences depending on how and whether we learn from it. The show includes works from Kehinde Wiley, now best known as the painter behind Barack Obama’s presidential portrait, and Tyler Mitchell, the photographer who shot his first Vogue cover, featuring Beyoncé, at age 23. But it’s another work in the show, by Hank Willis Thomas, that welcomes visitors to break another taboo of classic museum-going” taking a photo with a flash. His work, “Race Riot (With Interference), 2017,” is screen-printed on white reflective vinyl that obscures — whitewashes — a series of photos from a 1963 civil rights protest in Birmingham, Ala., that turned violent. The message is clear: You could stare at the white vinyl all day long, and it won’t tell you anything more about what it’s hiding; it’s only when you break a taboo and take direct action that you have any chance at uncovering the truth.

That’s a lesson I learn the next day, when I take a trip to the St. Louis Art Museum, a 20-minute Uber ride away in Forest Park, to walk through their latest special exhibition, “The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century”.

“The Culture” opened a few weeks after “Revival,” and demonstrated why 21c was so necessary. While there were works on display from celebrated contemporary artists, including Deana Lawson and Nina Chanel Abney, the show was less focused on the politics of hip-hop’s evolution from community to industry, and more focused on celebrating its commercialism. There were so many fuccboi fashion totems on hand, including Pharrell’s oversized Vivienne Westwood hat, a Louis Vuitton duffle bag designed by Virgil Abloh, Travis Scott’s Cactus Jack Jordans, mannequins dressed in Dapper Dan for Gucci and a reproduction of Chance the Rapper’s overalls, it was enough to make me think the show was low-key sponsored by StockX.

The biggest fail, however, may have been the inclusion of a painting by the Ethiopian American artist Julie Mehretu, best known for her paintings of unidentified landscapes abstractly notated with strikes and marks that may suggest a city planner’s sweeping intentions for dealing with urban sprawl, gentrification, demolition, exodus. Such subject matter would be a perfect fit for a show about the disenfranchised communities that birthed hip-hop culture. Instead, “The Culture” inexplicably features another Mehretu work, a portrait inspired by “The Tibetan Book of the Dead.”

An accompanying title card reads how the artist “drew inspiration from political graffiti” for the painting, and how graffiti is “one of the original pillars or elements of hip hop.” It’s a cynical reach, and the worst part is, the more relevant Mehretu landscape is hiding in plain sight just a few feet away in one of the museum’s free public galleries.

It’s yet another lesson that you’re always going to have to work a little harder for answers. And the lesson isn’t even free. A ticket to “The Culture” costs $12. At 21c, that could buy you a double.